Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Amnesia is a tricky term to understand because it is used in so many ways.

Amnesia is a tricky term to understand because it is used in so many ways.

For example, it has become popular to talk about “political amnesia” to explain the “crisis of memory” in various parties. Movies and streaming series also often feature characters suffering some form of memory loss and calling it “amnesia.”

But using the term amnesia in these ways muddies the waters of an already complicated topic.

So let’s bring some light to the field of forgetting as we explore retrograde vs anterograde amnesia in full, including some specific case studies from scientific literature.

Anterograde vs Retrograde Amnesia: What’s the Difference?

The difference is found in the prefixes.

Something that is anterior is situated in front of another object or event.

“Retro” as many of us know, refers to the past.

Therefore, anterograde amnesia refers to having difficulties forming memories after amnesia sets in.

Retrograde amnesia, on the other hand, refers to experiencing issues with accessing memories before the onset of amnesia.

Let’s dig a bit deeper and look at some specific examples. That way you can truly learn the difference between retrograde and anterograde amnesia.

What Is Anterograde Amnesia?

Christopher Nolan’s Memento, released in the year 2000.

According to clinical neuropsychologist Sallie Baxendale, this movie’s representation of anterograde amnesia is fairly accurate. As she explains:

“The film documents the difficulties faced by Leonard, who develops a severe anterograde amnesia after an attack in which his wife is killed. Unlike in most films in this genre, this amnesic character retains his identity, has little retrograde amnesia, and shows several of the severe everyday memory difficulties associated with the disorder. The fragmented, almost mosaic quality to the sequence of scenes in the film also cleverly reflects the ‘perpetual present’ nature of the syndrome.”

“Perpetual present” is a key term here because people suffering anterograde amnesia cannot lay down new memories.

Why does this happen?

Traditionally, scientists have thought that anterograde amnesia is likely caused by something interrupting the consolidation of new memories. Here’s how Dr. Michaela Dewar puts it in her contribution to the excellent book, “Cases of Amnesia: Contributions to Understanding Memory and the Brain”:

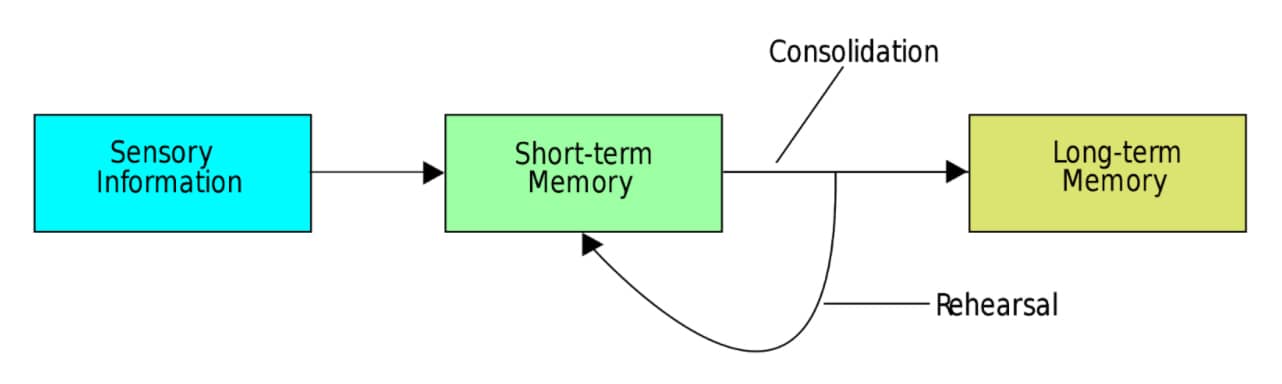

“During consolidation, new fragile memories become increasingly resistant to disruptions.”

Dr. Dewar’s research at Heriot Watt University’s Memory Lab suggest that more rest can help people suffering from anterograde amnesia.

Exactly what it is that interrupts consolidation remains unclear. Dewar suggestions it could be:

- A general malfunction in the automatic consolidation of new memories

- A lack of intention by the patient to voluntarily rehearse new memories

- Situations where the patient faces overwhelming amounts of sensory input

- Other, as yet unknown interruptions between encoding and retrieval of memories

A Specific Case of Anterograde Amnesia

Dewar herself reports the specific case of a patient with severe anterograde amnesia caused by limbic encephalitis. For privacy purposes, the patient in question is referred to as PB.

“The severity of his anterograde amnesia is perhaps best illustrated by a couple of anecdotes: when we first met, PB’s wife reported that a close family friend from abroad had recently been staying with them for several days. However, within minutes of the friend’s departure, PB had no recollection of the friend’s visit.

More strikingly, after an hour of interviews and neuropsychological assessments, I left the room for a couple of seconds and then re-entered to examine informally PB’s ability to remember me after a brief delay. When I returned, PB had no recollection of ever having met me before.”

Dewar found after working with PB that rest improved his ability to remember certain kinds of information.

“I was both excited and perplexed by these findings! How was it possible for people with severe anterograde amnesia to be able to retain so much new information over periods of up to one hour?”

Is There A Cure For Anterograde Amnesia?

Dewar’s best answer as of 2020 has been rest, something which seems to have enabled PB to recall certain kinds of information even when his attention was diverted to other topics.

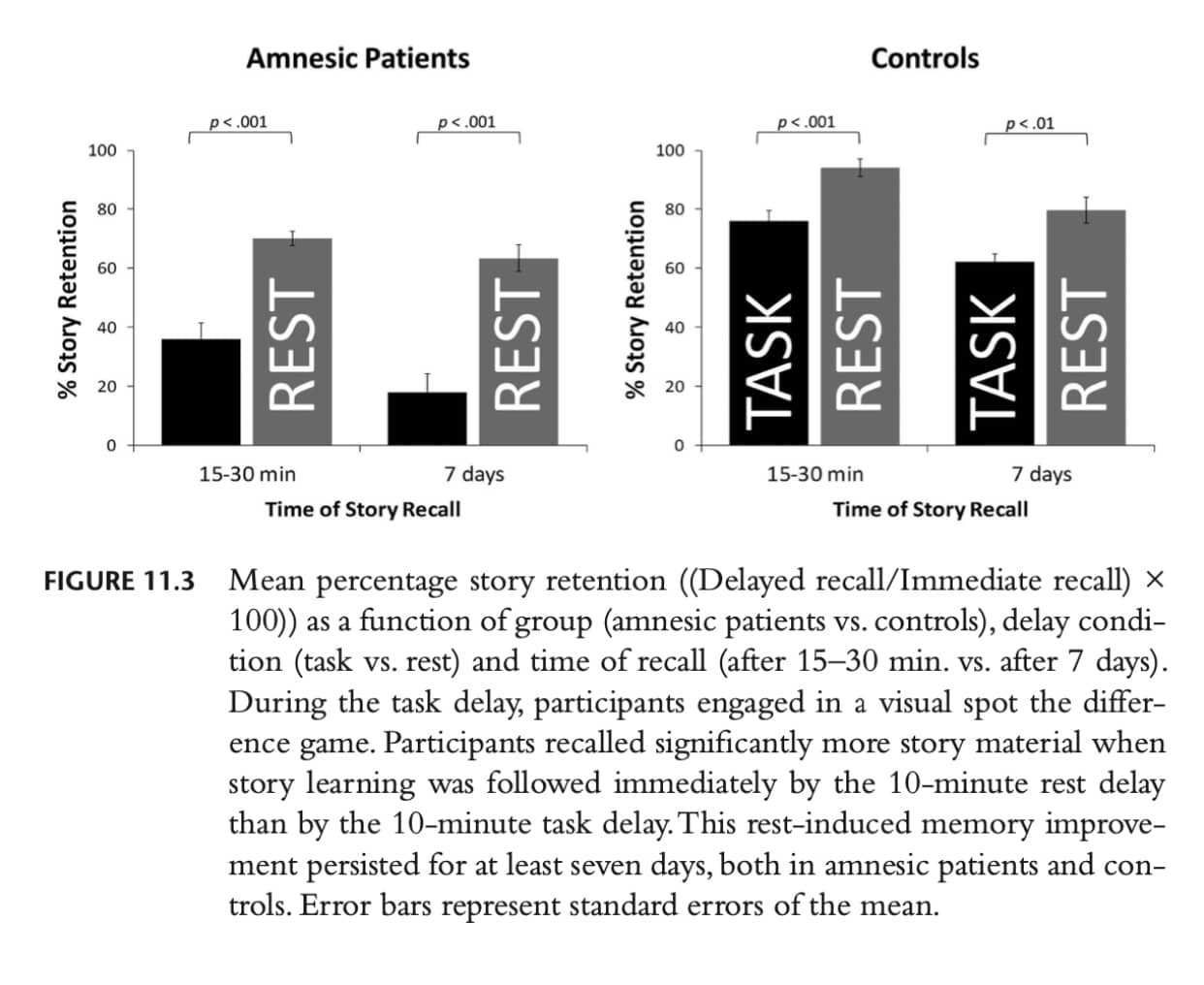

She is not the only researcher to conclude that rest is a potential solution for anterograde amnesia. It may even be possible to promote memory consolidation without patients needing to sleep. This was reported in a Neuropsychology journal article called “Minimizing interference with early consolidation boosts 7-day retention in amnesic patients.”

Finally, a lot of the answer depends on what exactly the patient is trying to remember. There’s a difference and it matters.

For example, according to senior lecturer Anshok Ansari, some people with anterograde amnesia will struggle with laying down new:

- Episodic memories (stories about life, events, etc)

- Semantic memories (facts, vocabulary, etc)

As Dr. Ansari has explained in a video for Sage, you can ask a person with anterograde amnesia for facts about France. They’ll be able to answer them correctly (semantic memory), but not be able to tell you what happened to them personally last week (episodic memory).

Can An Actor With Anterograde Amnesia Still Perform?

Further along in Cases of Amnesia, researchers Michael D. Kopelman and John Morton discuss the case of an actor with severe autobiographical memory issues. This case is especially interesting because many actors use their personal memories as the basis for forming their roles.

The autobiographical memory issues harmed this patient’s anterograde memory:

“His anterograde memory deficit was evident at the first learning trial, where he consistently performed worse than controls but, thereafter, he was able to learn and retain (for

use at subsequent learning trials) longer and much more complex material (in terms of syntax and semantics) than has been demonstrated previously.”

The research is very interesting because they challenged him with contemporary theater acting tasks and older texts, like Shakespeare.

Regardless of the text, the actor still did well in recalling his lines. However, he still could not remember much about his life:

“He said that he practised for approximately an hour to an hour and a half each day. He did not commit all the lines to memory, and did not carry out word-by-word learning. Instead, he said that he ‘thinks about the performance . . . how it will work best. . . . By reading aloud, I work on it.’ “

Despite this accomplishment, AB still had a severe amnesia in everyday life.

“For example, he could not recall at all a therapist whom he had met on approximately 12 occasions previously, and he had only vague recollection about another therapist, whom he had met on more than 20 occasions.”

As sad as this case of anterograde memory is for the actor’s personal memory, it is fascinating that he could still learn enough complicated material to perform in a play. This shows the importance of rehearsal in forming new memories.

What Is Retrograde Amnesia?

In Individual and Collective Memory Consolidation: Analogous Processes on Different Levels, researcher Thomas Anastasio defines retrograde amnesia as:

“Any loss of memory for events that occurred before the insult that caused the amnesia, and it may be induced in individuals through various neurologic or psychologic pathologies.”

In other words, with this form of amnesia, you can forget large amounts of your past, but still be able to learn and remember new information.

This form of amnesia can be caused by:

- Damage to brain structures from collisions

- Harm to the brain from substances like toxins

- Medicinal side effects

- Hippocampal damage from tumors

- Brain damage from conditions like encephalitis and meningitis

- Oxygen deprivation

- Psychological harms, such as trauma or even insults

In this form of amnesia, patients may suffer different effects. For example, they may forget:

- Many things or everything from before the onset of amnesia

- Material from a few hours before the onset

- Longer periods of time

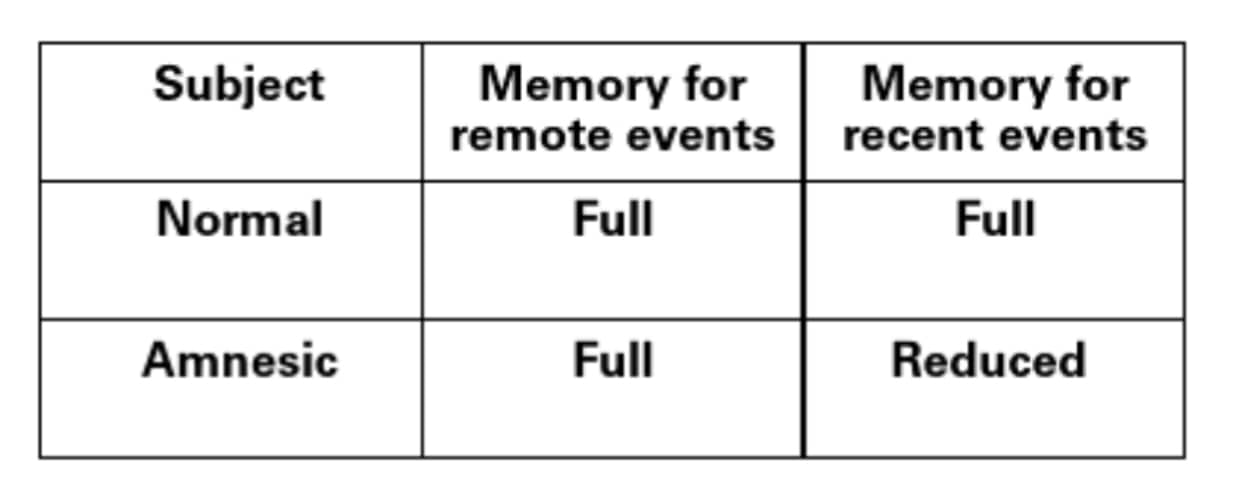

To help distinguish these kinds of retrograde amnesia, scientists use the terms “recent” and “remote.” The patient might suffer full or reduced forgetting.

A Specific Example Of Retrograde Amnesia

Here’s a very clear example of retrograde amnesia given in the book, Amnesia: Clinical, Psychological and Medicolegal Aspects.

“A woman of 34 began to show disturbances of behaviour while on a cycling holiday with her husband. She lost her way on familiar routes, would stop and wander off the road for no reason, and on two occasions temporarily lost her bicycle.

However, it was not until three weeks later that she developed headache, slight fever and a gross confusional state, at one time with hallucinations.

On examination at this time, she had some swelling of her optic discs and a marked lymphocytic pleocytosis in her cerebrospinal fluid, but no localized signs in the central nervous system.

As the general confusion and hallucinations subsided, mental examination showed a gross fixation amnesia with florid confabulation.

She recovered slowly, but it was over two months before she was fit to resume her household duties.

When seen nine months after her illness, she had a permanent retrograde amnesia which involved some six weeks of her stay in hospital and the preceding three weeks, with a sharp end-point at one particular incident of her cycling holiday.

Her memorizing was also persistently defective. She would lose things easily, forget household details and had difficulty in remembering acquaintances.

However, these defects were minor ones and she was able to lead a normal life and look after her home satisfactorily. She died some two years later of an unrelated condition.

At autopsy the brain was macroscopically normal. Histological examination showed evidence of localized perivascular cuffing in the floor of the third ventricle and extending a little into the periaqueductal region. No other abnormalities were found.”

Attempts To Understand And Cure Retrograde Amnesia

To understand how memory works, scientists often use models.

As with anterograde amnesia, the basic model requires understanding memory consolidation. It is a time-based process that transfers short term memory into long term memory.

You can think of memory consolidation as laying bricks. First you have a foundation, then you put down some cement. Into this cement, you align bricks and allow the cement to set.

Memory consolidation is the setting process. The more it functions in a stable way, the more you’ll be able to retrieve each individual brick in your “wall of memory.”

But when retrograde memory takes place, it’s not entirely clear what goes wrong, especially since some people are able to recover from it.

For example, in the book Amnesia cited above, people with retrograde amnesia from meningitis have recovered their memories when the illness was resolved. And as we’ve seen, they can still lay down new memories even while suffering from retrograde amnesia.

Other Causes Of Memory Loss

Sigmund Freud talks a lot about forgetting in his 1901 book, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. In brief, he suggests:

- Social forces cause us to repress things we wish to express

- Forgetting is one of the mind’s ways to prevent us from expression

- Forgetting may be “incomplete” leading to other problems, like resentment

Was Freud correct about these things?

Although he has fallen out of favor, many people can probably relate to efforts they’ve made to “forget” things that have irritated them. We have all gone out of our way to avoid launching our various criticisms for fear of “rocking the boat.”

But when you think about it, the Internet has made it possible for people to air any number of complaints, particularly through social media.

This form of collective activity has caused many people to wonder if we haven’t seriously reduced our collective attention span. In fact, it’s led to one German researcher coining the term “Digital Amnesia.”

There is definitely something to these factors and how our technologies have changed human memory. And there may well be a political price to pay.

As a collection of essays called Geopolitical Amnesia: The Rise of the Right and the Crisis of Liberal Memory argues, we may have entered an “age of forgetting.”

Part of the problem Vibeke Tjalve finds in the conclusion to this book is that we have externalized or offloaded so much human memory to machines that history has been “re-shaped, and re-circulated to an extent that ultimately threatens to render history itself without meaning.”

This is a serious criticism worthy of criticism. But is it really amnesia?

Let’s Stop Confusing Amnesia With Cultural Issues

At the end of the day, amnesia is a condition that harms individuals. It prevents you from either accessing your personal past or laying down new personal memories.

This condition must be devastating for the people who experience it. And all the more so when it becomes increasingly difficult to find clear definitions and extended examples.

Although I appreciate that there probably is such a thing as “cultural amnesia,” history is a big place. The Internet really hasn’t been around long enough for us to start calling its few historical disruptions by the name of what is effectively a serious disease.

I hope this article has helped you understand the differences between retrograde and anterograde amnesia. I also hope the examples have given you deeper insight into the nuances of each.

As we move into the future, let’s work together to use terms like “amnesia” very carefully. Real people with real issues need the best possible help they can get and definitions matter.

Related Posts

- What Is Autobiographical Memory: A Simple Guide

Autobiographical memory can be complex to understand. This article is packed with autobiographical memory examples…

- MMMP 009: Memory Training Consumer Awareness Guide

Here's an audio presentation of The Magnetic Memory Method "Memory Training Consumer Awareness Guide."

- How to Meditate for Concentration and Focus: A Simple Guide

In case you've ever doubted the awesome power of meditation for concentration, just wait until…

2 Responses

Fantastic Write up!

But I have some questions.

What amnesia can I call sluggish remembrance of all things (and recognising people that I have just met after some months of departure)? And how can I deal with it?

Because, as a teacher, I find it difficult to completely remember the assignment and even the number of works given to my students on my arrival of the next class.

More questions coming up!

Thanks for stopping by.

I would suggest running your question past a medical professional. It doesn’t sound related to amnesia to me.

Generally, you might want to look into brain fog, but again, after seeing a doctor first.

Hope this helps!