Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

I did not have to think about the route. I did not have to look it up on Google Maps.

The path from my favorite cafe to my apartment is laid out clearly in my brain. Every turn, every lane is distinctly mapped in my memory.

How can I do this?

It is my superpower. Voila!

Okay, that’s not correct. It’s not my superpower. We all have this superpower.

We all use cognitive maps or mental maps every day to navigate unfamiliar territory, give directions, learn or recall information.

In this post, I’ll explain what are cognitive maps, how do they work and how to use them in memory strengthening exercises like memory palaces.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

- What are Cognitive Maps?

- Importance of Cognitive Maps

- How do Cognitive Maps Work?

- Are Cognitive Maps Accurate?

- Are Cognitive Maps Different from a Mind Map?

- How to Build Memory Palaces with Cognitive Maps?

What are Cognitive Maps?

In brief, they are mental representations or images of the layout of one’s physical environment. That spatial representation can include the exact specifics of a location and the general area of a location.

As we interact with our surroundings, we interpret and encode them into mental maps or nodes of knowledge. We then use these mental maps or spatial information to travel to our favourite restaurant, nearest hospital or just get to the office.

We can also use mental maps to form powerful memory palaces and memorize anything. I’ll tell you more about this later.

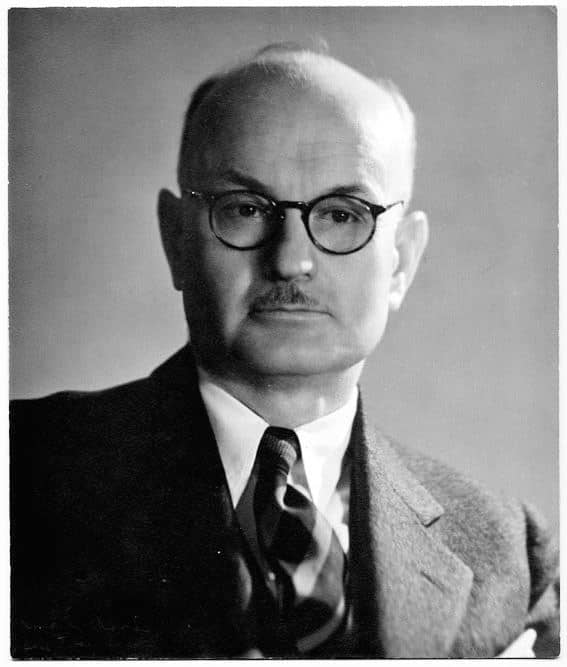

Coined in the 1940s by American psychologist Edward Tolman, cognitive maps are an internal spatial representation or mental model of the landscape in which we travel.

The term and the concept were introduced by Tolman in an article in the journal Psychological Review in 1948.

Cognitive maps are also known as mental maps, mind maps, schemata, and frames of reference. They are a small part of a person’s spatial cognition.

The branch of cognitive psychology that studies how you gain and utilize knowledge about your environment to identify where you are, how to obtain resources, and how to find your way home is known as spatial cognition.

According to D.R. Montello, in the International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2001:

“The cognitive (or mental) map includes knowledge of landmarks, route connections, and distance and direction relations; nonspatial attributes and emotional associations are stored as well.

However, in many ways, the cognitive map is not like a cartographic ‘map in the head.’ It is not a unitary integrated representation, but consists of stored discrete pieces including landmarks, route segments, and regions. The separate pieces are partially linked or associated frequently so as to represent hierarchies such as the location of a place inside of a larger region.”

Importance of Cognitive Maps

Cognitive mapping has a definite function. It is an essential skill for many living organisms, and it is the reason we do not get lost in places we have been in before.

Tolman believed cognitive mapping to be a type of latent learning where individuals acquire large numbers of signals or cues from the environment and use these to build a mental image of their environment or a cognitive map.

The fun part?

When you drive or walk the same route every day, you learn the locations of various objects and buildings and build mental models of these routes. The cognitive processes take place automatically. You are usually not cognizant of this latent learning.

Now when you need to find a building or object on that particular route, your cognitive mapping of that route comes into play. Your cognitive processes use existing knowledge of the environment to generate new knowledge or pathways to find the building or object.

You usually do not have a problem locating a familiar place, even if you have access to a wide range of mental models.

Cognitive Maps & Mazes

Edward Tolman’s experiments involving rats and mazes was how he was able to visualize the importance of cognitive mapping in the human brain.

Tolman placed a rat in a cross-shaped maze and allowed it to explore the maze.

After the rat had explored the maze for a bit, it was placed at one arm of the cross, and food was kept at the next arm to the immediate right.

Since the rat was familiar with the layout, it learned to turn right at the intersection to get to the food.

Next, the rat was placed at a different arm of the cross maze. Tolman was interested to see if there was a change in behavior.

Did it get lost?

No, the rat was still able to move in the direction of the food no matter where in the maze it was placed. Differences in the position of the rat did not matter. Tolman stated that this was because of the initial cognitive map it had created of the maze.

Tolman’s experiments with rats ingrained the idea of the cognitive map in cognitive psychology.

How do Cognitive Maps Work?

What is the process to design cognitive maps in your brain?

Your brain creates a cognitive map using a number of sources. It uses visual stimulus and other cues like olfaction and hearing to deduce your location within an environment as you move through it.

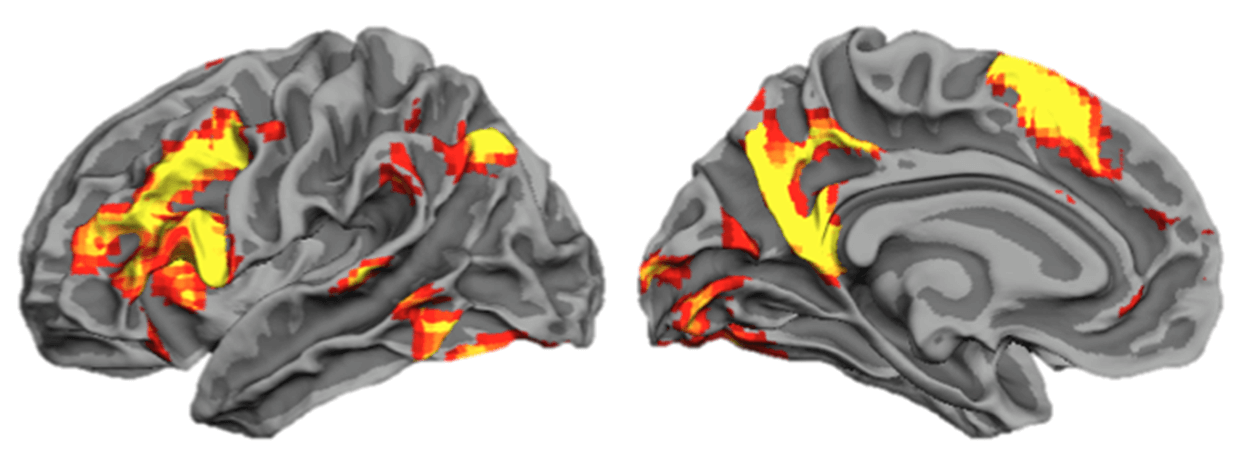

Using these cues, a vector is created that represents your position and direction within an environment. The vector is then passed to the hippocampal place cells where it is interpreted, and the brain gets more information about the environment and your relative locations within the context of the cognitive map.

The entire activity may seem complex, but it happens almost automatically.

The Hippocampus As A Cognitive Map

Interestingly, both birds and mammals form cognitive maps using the brain’s hippocampus.

In The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map (1978), neuroscientist John O’Keefe and neuropsychologist Lynn Nadel, say that neurons in the hippocampus form a memory of the animal’s environment. Then when the animal goes to that particular place, these neurons are reminded of that place, as if they were reading from a map.

The book provided a more allocentric interpretation of the cognitive map.

Other studies by Torkel Hafting and Marianne Fyhn – part of a team headed by Edvard and May-Britt Moser at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology – discovered the existence of grid cells in the brain. They used techniques mastered by O’Keefe to study inputs to the hippocampus.

The researchers found a new type of spatial cells in the entorhinal cortex. The entorhinal cortex is the part of the brain that sends more information to the hippocampus than almost anywhere else. Surprisingly, the researchers found that these cells fired only when the rat went into specific places in the environment and that they fired in many places.

More interesting still, these cells formed a hexagonal pattern in which each firing place was the same distance from all its neighbouring ones.

The study led researchers to the discovery that metric information is inherent in the brain, wired into the grid cells, regardless of its prior experience.

The discovery proved to be both surprising and dramatic discovery. Scientists drew an important inference. They now understood that the hippocampus is both a map and a memory system.

Does Cognitive Mapping Use Memory?

Cognitive mapping uses spatial memory, but it is more than that.

Spatial memory records information about one’s environment and spatial orientation.

Now, here’s the most important point to understand:

The fact that you can retain the sequence of streets in the directions to your house is spatial memory.

However, when you see these streets in your “mind’s eye” as you give directions – that is cognitive mapping.

Are Cognitive Maps Accurate?

Cognitive maps are not completely accurate.

When you create a cognitive map, your brain will omit information that is irrelevant to the task at hand.

For example, you and your colleague, who lives in the same apartment block, take the same route to drive home daily. However, while you are in the driving seat, your colleague has a driver.

So, while you may be able to describe the route from the office to home accurately, your colleague may have a more basic idea of the road and objects en route.

Why?

Because he does not have to concentrate on the road during the drive, whereas you must.

Therefore, both of you sketch maps of the same route differently. The example also shows that travel modes can impact cognitive mapping.

The way people travel has a huge impact on your cognitive mapping – especially if they regularly use neurobics.

Understanding how the brain processes and sketches cognitive maps has important implications for transportation planners and accessibility planning in cities.

What this also means is that a cognitive map can be different from the actual environment that a person is mapping due to the relationships of an individual with the environmental stimuli.

Furthermore, the way spatial knowledge is represented in your mind leads to certain patterns of distortions. Spatial knowledge in the human brain is not as well modeled as the Euclidean geometry of high school math. For example, people often think the distance to go from A to B is different than from B to A.

Moreover, cognitive maps generally get distorted by simplifying assumptions, beliefs and preconceptions. For instance, in your cognitive maps, all roads may join at right angles or straight lines even if they do not do so in the real-world.

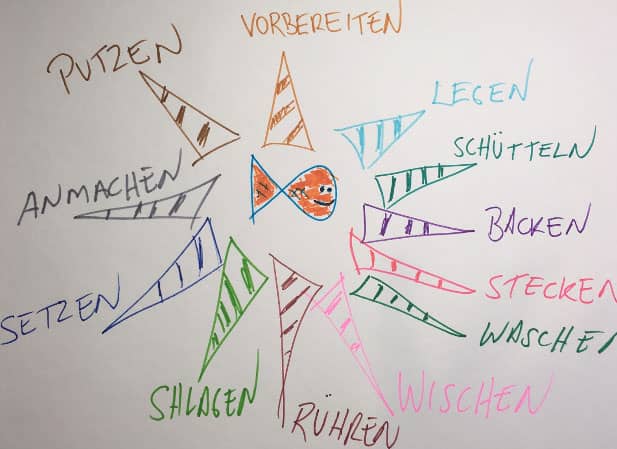

Are Cognitive Maps Different From a Mind Map?

When it comes to the real of ideas, mind maps do relate. You can think of them as the most simplistic and straightforward type of cognitive maps.

They are quick to create and have a clear hierarchy and structure. A mind map is akin to a tree with branches, where the bark represents a central topic, and the branches denote the subtopics.

In mind-mapping, the map represents information and ideas that are connected to each other. Such connections enable you to retain and learn new things quickly and easily.

Mind map “links” are usually “dynamically passive” – they don’t represent anything more than connectivity used for creativity and enhanced memory. To get really good, I suggest you check out Tony Buzan’s Mind Map Mastery.

In cognitive mapping, a model of the world is created using links as well as concepts. Moreover, cognitive mapping also uses links more actively than mind mapping. But the larger point involves strategy, which is what we’ll cover next.

How to Build Memory Palaces with Cognitive Maps?

Can these special maps in your brain enable you to find and build memory palaces?

Absolutely!

Here’s how:

As you form new cognitive maps of places you visit or recall your childhood home, college dormitory, a beloved first apartment, or your current residence, try to use them as multiple Memory Palaces.

Seen a new movie or read a new novel?

Use the layout of the fictional character’s home or environment to create your own mind palace.

Think the tiny home of Frodo Baggins from Lord of the Rings or Monica’s iconic New York apartment on Friends.

In sum:

Just use your natural ability to form mental maps to build strong memory palaces and you can remember anything that you want.

Ready to get started? If not, let me know your questions and let’s get you more clarity so you can!

Related Posts

- How To Build Virtual Memory Palaces & Use Them For Learning

Have you ever wanted to build a virtual Memory Palace based purely on fantasy and…

- How to Improve Memory: 18+ Proven Memory Improvement Tips

Do you want to know how to improve memory? This ultimate guide delivers 18 actionable…

- 15 Secrets To Expanding Your Mind And Accessing More of Your Brain

You want to expand your mind but don't know how. These 15 secrets show you…

2 Responses

Hi Anthony. Thanks for the podcast, loved it. I am going to try it today. The Magnetic Memory Method has been very helpful to me, especially in my studies. Thanks for the great work.

From India, Anubhav.

Thanks for your post, Anubhav. I’m excited to hear that you’re finding the MMM helpful. What are you studying?