Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Want to know why concrete thinking is so difficult to define?

Want to know why concrete thinking is so difficult to define?

It’s because people use the term in many different ways. I observed this for years while teaching critical thinking as a professor.

To this day, I observe multiple uses as people regularly ask me for help in making their minds more practical and their memory skills sharper.

Here’s something else a bit strange that I’ve encountered as a memory expert: People will ask me to help them remember “abstract” concepts, thinking that abstract thinking is somehow the opposite of concrete thinking.

But is that really the case?

Not always.

You actually can experience some incredibly concrete abstractions. Flags, for example, represent entire countries at an abstract level. Yet flags are also incredibly concrete.

So what gives?

If you’re confused, don’t worry. We’re going to get to the bottom of things on this page.

That way, when people say things to you like “concrete thinking is literal thinking,” you’ll be able to respond…

“Yes, it is that, but also so much more.”

Are you ready?

Let’s dive in!

What Is Concrete Thinking?

The first thing we need to understand is that thinking is always about representing knowledge.

The world is a very complex place, but for the sake of simplicity, we can boil our experience of it down to three kinds information:

- Material

- Conceptual

- Experiential

When it comes to the experience part, many people cite Jean Piaget as an expert in concrete thinking. However, I believe this is a false attribution.

Here’s why:

Piaget was really talking about something called concrete experience.

In the first of his four stages of development, he discusses Sensorimotor development, which takes place between birth and the age of two. There is not necessarily anything related to thinking as we normally mean it going on during this period of life.

Rather, the goal of the child during this stage is to establish what is called “object permanence.” In other words, the child “remembers” that objects exist even when they are outside of awareness.

Concrete experience with objects is needed for this to take place.

It’s only during stage 2 that symbolic thought, which involves abstract thinking begins to emerge. Later, logical thinking and then scientific reasoning develop at different levels depending on the individual’s context.

So with Piaget out of the way, let’s look at what really defines concrete thinking.

The Real Definition Of Concrete Thought

I believe Maxine Anderson puts it best in a book called, Absolute Truth and Unbearable Psychic Pain:

“Simply put, the concrete state of mind relates to reality in terms of sensory perception and sensory experience, defining reality in terms of what the peripheral senses convey. More specifically it is a state of mind in which metaphor and symbolic thought are not available.”

Researchers have generally agreed. In this study, for example, the researchers found that you have to bring a “concretizing mindset” in order to help define what you’re experiencing.

To better understand the need to literally work at making your thoughts about an experience concrete, try this exercise:

Place an orange in your hand. Think about how it feels in your hand and how it will taste.

Those are concrete thoughts. Although an abstract thought about how much the orange weighs or what country it comes from might arise, thoughts about feelings and taste are based on your concrete experience of stimuli in your immediate environment.

3 Concrete Thinking Examples

Other lists of examples claim that “concrete thinkers” don’t understand phrases like “it’s raining cats and dogs.”

Frankly, I’m not sure if that’s true. If some people can’t understand or relate to popular idioms, other issues may be involved, such as literacy levels, reading comprehension and sufficient practice with self-expression.

So with the immediacy of your physical senses in mind, let’s look at some more examples. These will help better illuminate the concrete thinking process.

One: Visible Thinking

Although Visible Thinking is a book for mathematics teachers, I believe its key points apply to all kinds of thinking.

The authors basically point out that even the most abstract and conceptual concepts can be made concrete by:

- Speaking them out loud

- Hearing others discuss them

- Drawing them on a chalkboard

- Writing about them in a journal

Memory expert Tony Buzan was a huge proponent of visual thinking. His style of mind mapping has helped thousands of people turn complex ideas and processes into immediately graspable form. Using a mind map is one of the best ways to feel and see anything you find abstract in a concrete manner.

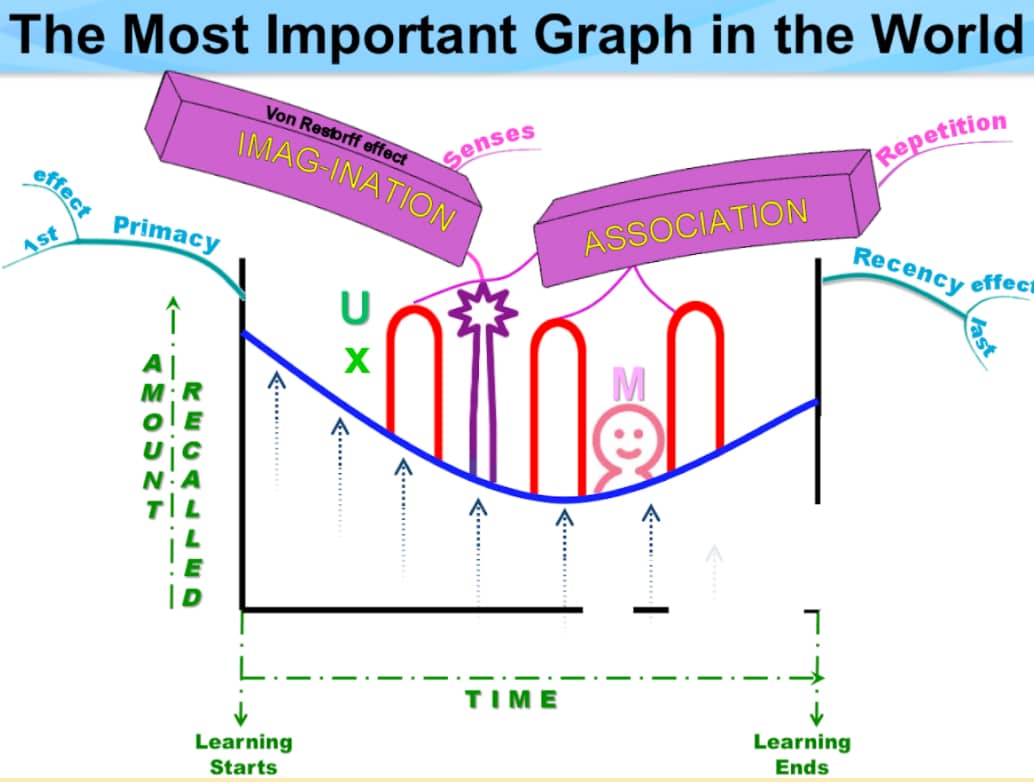

One example is how Tony taught the rules that govern memory by having all of his students draw what he called The Most Important Graph in the World.

It’s a simple concept, but has a lot of moving parts that can be difficult to understand when conveyed in writing alone. I never fully understood it myself until Tony had me draw it out in my own handwriting. Now this knowledge is very concrete in my mind because something about how visual memory works was amplified by the drawing process.

You might think that my experience is an isolated example, but that’s not the case. Researchers have found that creative drawing does indeed assist memory and comprehension. Other researchers are working on ways to have this kind of concretizing learning strategy spread more widely so more learners can benefit.

Two: Relationships (In Life And In Art)

Ever found yourself attracted to a person but you don’t know why?

The philosopher Immanuel Kant called this die Verwandtschaft in German. It means “affinity,” “relatedness” or “kinship.”

The German poet and novelist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe even wrote a novel about this concept, Die Wahlverwandtschaften or Elective Affinities. In this novel, Goethe used principles of chemistry to explore whether or not human relationships like marriage follow certain concrete, biological rules.

No matter where you stand on such divisive topics, you’ve probably felt your heart race when you’ve been attracted to someone. You’ve probably experienced the instinct to protect a sibling or close friend.

The thoughts that occur during such situations are immediate, primal and perfect examples of what we really mean by concrete thinking.

We know that Goethe had the concrete in mind because he wrote Elective Affinities using a style of literature called Weimar Classicism. Although abstraction is part of this form, through the principle of Stoff, writers using this style worked assiduously to make sure even the highest concepts were firmly attached to immediate aspects of concrete reality.

Three: Concrete Contemplation

The goal of Zen and many other contemplative traditions is to live in the here and now.

Does it get any more concrete than that?

Not really, especially when you read the research showing that people with depression tend to think more abstractly than those who don’t. Whether it’s Zen or Stoicism, thinking concretely for contemplative purposes is very useful for many aspects of psychological health.

How does it work?

In Zen, the practitioner typically focuses on a koan. It is a question or statement that helps you experience doubt about the authenticity of your mental world. As you reflect on the koan, you become deeply embedded in the physical nature of the present moment.

One of my favorites comes from the Blue Cliff Record and you can immediately see how concrete it is:

Student: What is an example of an enlightened person?

Teacher: Two eyes in a skull.

I have personally benefited a great deal from this kind of koan-based concentration meditation. In this case, you have to think a little about what the koan is saying, and there’s more than one possible interpretation. For me, it basically means that all people are enlightened. They just don’t necessarily see it yet.

How specifically is concrete contemplation like this helpful?

Personally, my mind used to be so undisciplined that I hardly noticed what was going on around me at all. The “object permanence” of my own body was so lost to me that I would forget to eat for hours on end, not to mention other forms of neglect.

But then I learned these two questions that stop unwanted, abstract thinking. I’ve been much more focused on the concrete present as a result.

Researchers have discussed why meditation might create this effect. In this study, for example, it boils down to how meditation improves our ability to pay attention. Nothing is more concrete than being present to what’s going on around you, it seems.

And it makes sense too. You can’t use analytical thinking at all to help reach concrete conclusions you aren’t paying attention. This is a point memory expert Harry Lorayne made countless times throughout his long and successful career.

Concrete vs Abstract Thinking: What’s the Difference?

The main difference between concrete and abstract thinking is scale.

Whereas concrete thinking is firmly located in the immediate here and now, based on the senses, abstract thinking goes much wider.

For example, if you are a concrete thinker reflecting on environmental issues, you might focus only on yourself and your family. An abstract thinker will extend to think about entire communities, possibly the entire world population and even compare macro and micro scales at the same time.

An abstract thinker will likely also think about different historical periods and compare environmental data and predict future outcomes. This is obviously very different from the concrete thinker who focuses solely on the next few days or weeks ahead.

Of course, it’s entirely possible to think at both levels of scale. In fact, we must if we want to survive.

Exercises to Help You Improve Your Concrete Thinking

Now that we’ve established what concrete thinking is and what it isn’t, let’s look at some ways to improve how you use this most important of all the main types of thinking.

Forgive the pun, but this is where we will pour the foundations and cement them into place.

Reproduce A Painting In Your Mind

What could be more immediate and material than mentally recreating a painting that you’re familiar with?

The steps are simple:

- Close your eyes

- Bring the painting to mind

- Imagine painting it with your own hand

- Focus on all the individual colors

- Verbally describe different contours

- Imagine moving into the painting and towards the vanishing point

Repeat this exercise often with other paintings.

And for bonus points, explore art galleries and art books so that you have even more references to use.

Hilbert’s Hotel

David Hilbert thought a lot about infinity. It’s one of the most abstract concepts we know.

The Hilbert’s Hotel exercise asks you to imagine infinity as an endless series of hotel rooms, each one occupied.

However, you need to make room for one more guest. To do so, imagine each guest moving one room down, leaving the first room in the hotel empty.

As you play around with this:

- Explore how you imagine this hotel (one floor, many floors?)

- Physically feel the movement of the guests as they move to the next room

- Hear the sounds in your ears

- Experience any emotions (like being disgruntled when you have to move)

For bonus points, try to “double” infinity. In this version of the exercise, you have the guests move two rooms instead of one.

The Wealth Exercise

In a famous story called The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, Ursula K. Le Guin describes a world in which one child suffers terribly so that others might thrive.

Read that story and then to complete this exercise, imagine that you are the richest person in the world.

Explore the moral dimension of how that feels.

What responsibility do you have to help others? What does that responsibility feel like?

What responsibility do you feel that others have to care for themselves?

Once you’ve explored these ideas, write a 200-250 word essay response to the classic Wayne Dyer statement that all the money in the world will never solve poverty.

Is he right or wrong? Defend your answer.

The Separate-Less Exercise

Greg Goode provides many great concrete sensation exercises in his books.

For example, he describes an exercise with an orange where he asks you to find yourself as the observer while examining a piece of fruit.

Although this might seem counterintuitive and abstract, it’s very hands one. What Goode is essentially asking you to do is realize that your experience is the most concrete thing any of us has access to.

To complete the exercise:

- Put an orange on a table or in your hand

- Describe exactly what you are actually seeing in terms of colors and shapes

- Ask what is it that differentiates the table from the orange

- Notice that there is nothing in the visual display that says “table” or “orange”

- Ask yourself, why do you know these terms?

As you go through this process of inquiry, different memories might arise about how you have been effectively trained through education to think in particular ways.

Don’t be alarmed. You’re using concrete thinking to encounter just how cemented into social conventions your life has been all along.

Concrete Thinking Is Consciousness

If there’s one major takeaway I hope you’ll get, it’s that you are experiencing the present moment in a concrete way each and every second that passes.

However, most of us are lost in a very abstract set of thinking processes that pull our attention away from the concreteness of the present.

Or are we?

If you take the orange exercise one step further, is it really true that our absent-minded thoughts are somehow the opposite of concrete thinking?

Just because we get lost in thought doesn’t mean we’re somehow not experiencing lost-in-thoughtness itself in a non-concrete way.

In other words, it’s still a conscious experience in the same way dreaming is an immediate and real experience.

When you take this realization into your everyday life and use memory techniques like the Memory Palace, life will feel much more immediate and satisfying. It was more concrete than you realized all along.

And if you need more help in making abstract ideas concrete, I suggest you sign up for this free course:

So what do you say?

Are you ready to start experiencing the world of your mind in a new and more concrete way?

Bring it on!

Related Posts

- Abstract Thinking: What It Is and How to Improve It

Need to master abstract thinking? Learn the exact definition of abstract thinking and what makes…

- The 10 Main Types Of Thinking (And How To Use Them Better)

If you need to learn the main types of thinking with specific and concrete examples,…

- 9 Deadly Critical Thinking Barriers (And How to Eliminate Them)

Most barriers to critical to critical thinking are easily removed. Read this post to boost…