Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The quick answer is yes, Memory Palaces absolutely do work.

The quick answer is yes, Memory Palaces absolutely do work.

Scientific studies consistently show us that using this ancient memory technique enhances memory recall.

Students in specialized fields love them because this technique works especially well for ordered lists, complex information and any learning goal where you need to establish long-term retention.

The catch?

Using this technique requires a bit of setup.

How much depends on where you currently find yourself in life.

For some people, mastery takes an incredibly short time.

In other cases, I’ve seen students try to learn the technique in bits and pieces. As a result, it’s taken longer than necessary.

Either way, the evidence stands in favor of the technique.

So does the thousands of years of tradition and the decades of memory competitions.

But it really wasn’t until 1885 that the first scientist truly put memory to the test.

Starting with that groundbreaking study, let’s look at what researchers have found since.

Do Memory Palaces Work? The Essential Evidence

Noting that the use of Memory Palaces goes back thousands of years, earlier even than the method of loci discussed in Greek and Latin training manuals like Rhetorica ad Herennium, it was Hermann Ebbinghaus who helped us first understand why this technique works.

Thanks to his research on memory in the 1885 book, Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology, we now have incredibly useful terms.

These include the primacy effect, recently effect and a memory strategy called spaced repetition.

This term describes a specific review pattern you can use to overcome what Ebbinghaus called “the forgetting curve.”

As his n=1 experiments showed, we lose 50-80% of information at a steady rate unless we review it.

One of the best ways to defeat the forgetting curve?

The Memory Palace technique for studying.

You can literally use the technique for studying just about anything.

Even shapes.

Gordon H. Bower’s Analysis of a Mnemonic Device

Between Ebbinghaus and the late 1960s, I’ve been able to find very little research that touches upon the classic Memory Palace technique.

Partly, that’s because the proof was already abundant in how people practice the technique. But scientists of the mind were also pouring a lot of their attention towards topics like subliminals for memory and other types of subconscious influence.

In 1970, Gordon H. Bower published “Analysis of a Mnemonic Device,” returning attention to this ancient memory technique.

He asked a lot of interesting questions about the technique and included fascinating illustrations in this American Scientist article.

For example, he showed how this mnemonic device works by showing tomatoes splattered on the door of a home.

A person would image such a scene to help themselves remember tomatoes on their shopping list, for example.

To make it work, the user would simply ask, “What was happening to the door?” and the scene would bring back the target information.

As Bower puts it, the technique works because:

“The loci on the list are well learned and are easily called to mind. Recall of the scene constructed at each locus enables him to recognize and name the other object in it.”

Bower is exactly right and that’s why I always tell people taking the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass to use locations familiar to them.

You certainly can use imaginary and virtual Memory Palaces. But you risk adding additional cognitive load that isn’t technically necessary.

Although neurological evidence was slim when Bower produced this scientific article, he used the memory science on hand to hypothesize that part of this techniques success boils down to left hemisphere brain activity and verbal ability.

Routes to Remembering by Eleanor Maguire

The Memory Palace technique is all about assigning memory spaces for whatever it is you want to learn.

Along with her team, Eleanor Maguire cut to the chase on that point when they named their Nature article, Routes to Remembering: The Brain Behind Superior Memory.

To conduct the study, the researchers enlisted eight memory champions.

Using brain imaging, they were able to determine that people who had developed superior memory skills showed specific differences.

The test examined the mental athletes on numbers, faces, and even snowflakes.

With all three information types, the reason for the benefits was clear:

The memory champions had well-practiced spatial memories thanks to using the Memory Palace technique.

Building a Memory Palace Within Minutes by Eric Legge

A lot of people worry that it takes too long to develop Memory Palaces.

Scientists have wondered about the time investment issue too.

In Building a Memory Palace Within Minutes, Eric Legge and his team created a virtual environment and tested it against traditional Memory Palaces.

The researchers found that, although their artificial Memory Palaces worked without taking up much time for the participants, these provided Memory Palaces did not improve anyone’s results.

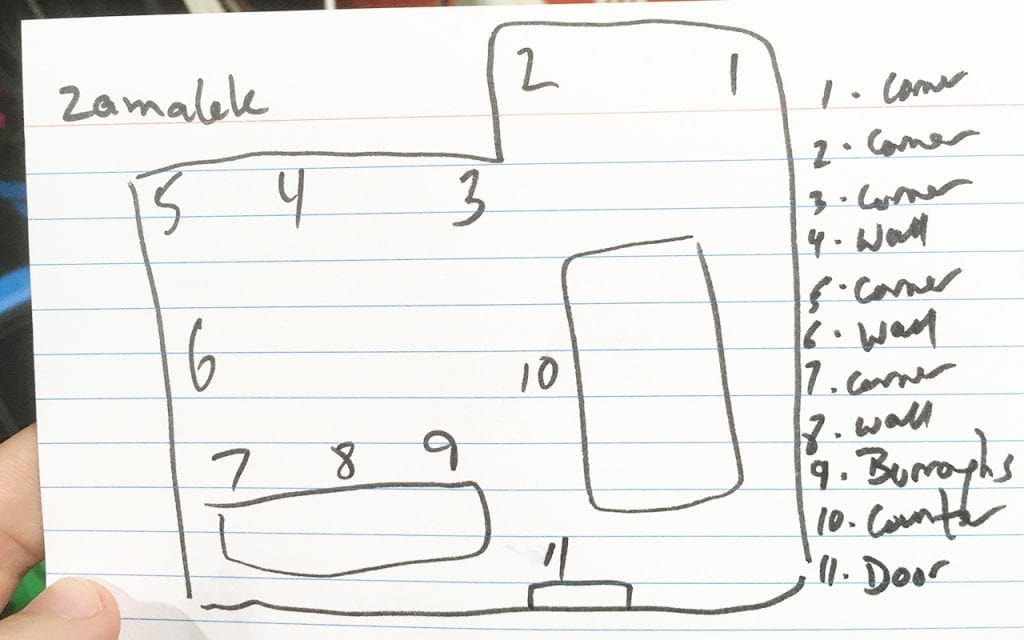

As I interpret their research, you’re better off sketching your own Memory Palaces based on locations you’re familiar with. Like the one you see in this illustration:

This difference is important because a true Memory Palace is not something you’ve memorized.

As the Maguire research suggests, a true Memory Palace works so well for a simple reason. It harnesses the power of spatial memory and locations you’ve already automatically learned.

It’s by basing your use of this technique on how memory works that makes the biggest difference outside the laboratory.

Studies of Medical Students Using Memory Palaces

A few years ago, researchers at Monash University tested Memory Palaces on medical students.

Both head researchers appeared on my podcast to discuss the study and you can still listen to both David Reser and Tyson Yunkaporta share their interpretations of the results.

The study itself is well worth reading.

And when it comes to research showing how well these techniques work for medical students, there’s plenty to pick from. For example:

- Pharmacology Retention and Evolving Memory Palaces

- Facilitating learning in endocrinology

- Studying dermatology

And there are many more.

One point about this dermatology research is interesting. It’s something you also find in the Monash University research:

Researchers supplied the participants in these studies with not only Memory Palaces but also mnemonic images.

This feature of their research raises an interesting question: Has anyone studied the difference between Memory Palace locations that researchers give you versus the ones you develop on your own?

The answer is yes.

Accuracy in a Virtual Memory Palace by Jan-Paul Huttner

Jan-Paul Huttner and his research term put out Imaginary Versus Virtual Loci: Evaluating the Memorization Accuracy in a Virtual Memory Palace.

We’re getting a bit into the weeds of mnemonic technique here, but these researchers report that participants using a pre-designed Memory Palace showed better results.

Frankly, I find the results problematic.

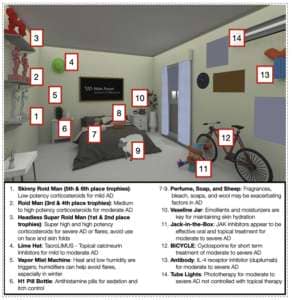

For one thing, this study and a similar study called Virtual Memory Palaces: Immersion Aids Recall both involved participants memorizing information of limited importance. Have a look at the following virtual Memory Palace:

Do you recognize Oprah, Napoleon, Shrek, Martin Luther King and Stephen Hawking in this Memory Palace?

I sure do.

Give how famous these faces are, I’m not convinced the Memory Palace is adding much in this experiment.

At least the Monash University research used challenging information related to anatomy.

Ultimately, I’m glad researchers have tested virtual Memory Palaces and shown an effect. But I await further tests using much more robust information before accepting that they work “better” than traditional Memory Palaces.

One reason I predict they won’t beat traditional Memory Palaces is cognitive load. Another reason is that studies in active recall have shown the importance of personalization in learning.

I’ve Used Memory Palaces to Learn Languages, Deliver Speeches, Ace Exams … And So Have Countless Others

We often hear about memory competitions and the people who win them.

Sometimes these memory athletes go on to inspire us, like Joshua Foer with his book, Moonwalking with Einstein.

Others contribute new variations on old techniques, like Dominic O’Brien did with the Dominic System.

Or, Memory Palace experts expand their teaching to include other techniques like Tony Buzan did with Mind Map Mastery (one of my favorite books on learning).

Some of my favorite testimonials have come from students who successfully passed critical exams.

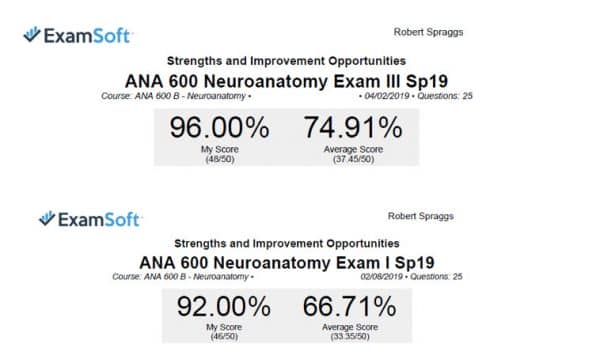

For example, Robert Spraggs shared his exam results from a difficult set of neuroanatomy exams:

As you can see, he wound up far ahead of the class average thanks to using Memory Palaces.

Myself, I’ve used the Memory Palace for language learning many times.

A while back, I completed Level III in Mandarin.

I was especially pleased by the results because I’m not all that young anymore. The classes started at 6 p.m., and that’s when the final test took place.

Nonetheless, I aced it, all thanks to using this technique.

How to Get Started with Memory Palaces

From my perspective as someone who has been using these techniques personally for decades and teaching them now for fifteen years, you’re best of learning to make your own Memory Palaces.

True, some of the studies show that you can use Memory Palaces created by others.

That’s totally fine if that’s the way you want to go. The only book I’ve seen that reasonably shows you how to use someone else’s imaginary location is Kevin Vost’s Memorize the Stoics.

Here’s what one of his Memory Palaces looks like so you know what you’re getting into if you go that route:

Personally, I’m glad I developed my skills the old fashioned way and learned how to come up with endless Memory Palace ideas.

I learned a lot about how to do that and use various aspects of the technique from ancient memory masters like Robert Fludd and Giordano Bruno.

Call me old fashioned, but I find that the creators of newer books and courses are so in a rush to make a buck that they dumb everything down.

Even Harry Lorayne told me to never talk about memory science if I wanted to make a career out of teaching these techniques.

Ignoring Lorayne’s advice is one of the best decisions I’ve ever made, especially when we take the results of the Flynn Effect into consideration.

Studying the scientific reasons why Memory Palaces worked in the ancient world (and still work today) has helped me better explain them to modern students. All ships have risen as a result of not walking away from the facts provided by research.

As a result, a lot of people have gotten better results than the books and courses designed for mass consumption.

So that’s my first suggestion: Find the real deal books on Memory Palaces.

Read them thoroughly and spend at least 90-days exploring their specific instructions.

Then, apply your well-formed Memory Palaces to specific goals. For most of us, we will be applying them to some kind of studying.

That’s why I make detailed video tutorials like this for you:

Once you’re done creating a few well-formed Memory Palaces, your next task is to learn the various systems for association:

There’s a bit of overlap between those mnemonic systems, but they’re all worth studying.

If you’d like help, feel free to get my free memory improvement course:

It gives you a massive head start with four detailed video tutorials and three worksheets.

And now that you know Memory Palace work, it’s just a matter of starting small.

You’ll exercise your spatial memory as you go. Not mention your reasoning skills and more.

As the research demonstrates, when you do this, you can easily reach memory champion levels of absorption and retention.

The only challenge I find some people have is in making the images they place inside of Memory Palaces bizarre enough to trigger recall.

But that’s where my free course comes in.

And rest assured, at more subtle levels of skill, you don’t have to keep making things so strange. The Memory Palace I used for my TEDx Talk was actually very calm.

Again, the key is just getting started. Is there any other way to start on the path to mastering this ancient art and unlocking your brain’s potential?

Related Posts

- Tap The Mind Of A 10-Year Old Memory Palace Master

Alicia Crosby talks to us about how she memorized all of Shakespeare's plays in historical…

- MMMPodcast Episode 001: 5 Ways To Ruin A Perfectly Good Memory Palace

In this session of the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast, I talk about the 5 ways…

- How to Use Superheroes In A Memory Palace To Learn Faster

If you know Batman, you can use him to help you memorize foreign language vocabulary…

4 Responses

I have retired after 51 years of full time employment and looking forward to using the memory palace in learning ancient music lyrics in latin and other languages. Looking forward to the results and I am always happy to hear about your latest books on method and research.

Thanks again Anthony!

Thanks for sharing these exciting goals, Faith.

Power to your journey and looking forward to any updates you have time to share along the way!

Enjoyed

That’s great – thanks for letting me know!