Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Learning how to teach yourself can be fast, fun and incredibly effective.

Learning how to teach yourself can be fast, fun and incredibly effective.

It can even be relatively inexpensive.

But discovering how to learn on your own can also be psychologically and financially disastrous if you go about it the wrong way.

Whether you’re looking to advance your career, enrich your personal life, or simply satisfy your curiosity, there definitely is a right way to go about educating yourself.

And make no mistake:

In today’s fast paced world, you can’t afford to make too many rookie mistakes.

I know this all too well from my experiences getting a PhD, learning languages and figuring out how to reach millions of people through books, video courses and this blog.

My journey has been filled with mistakes that you can avoid by reading this post.

I’ve taught at three universities too and seen many learners make enter irrelevant learning mazes.

But because I’m so passionate about helping my fellow lifelong learners, I’m delighted to at least try and help you avoid the dead-ends and save time as you harness the power of learning on your own.

Ready for my best tips?

Let’s dive in!

How to Succeed Along Your Solo Learning Journey: 9 Powerful Tips

Learning on your own starts with four core commitments:

- Creating and reviewing a vision statement that guides your journey

- Deep engagement with topics and skills beyond surface-level understanding

- Critical thinking about which accelerated learning techniques are worth pursuing

- A long-term investment in active learning strategies

You need these commitments because it’s all too easy to feel like you’re involved in serious autodidactic efforts.

But if you want to become a polymath and master several skills and topic areas, especially if you lack the most common polymathic personality traits, you can’t afford to rely on your feelings.

As this peer-reviewed study demonstrates, many learners think they’ve learned much more than actually did because of how passive learning feels.

Although it’s true that the passive consumption of information is comfortable and often fun, it’s usually a dead end for self-learners.

We actually learn better through active engagement. And that means feeling challenged, which is a different sensation than understanding or even remembering something.

The lack of alignment found in the University of California study I linked you to above is not new. St. Augustine addressed this problem long ago, as did a very important medieval mnemonist named Hugh of St. Victor.

With the need for active learning in mind, here are my best tips for making sure all of your self-learning activities keep you challenged and deliver real results.

Ignore them if you choose, but please understand that without most of them in action, you risk learning little or nothing.

One: Spend An Epic Amount of Time Structuring Your Goals

A lot of people claim that S.M.A.R.T. goals can help keep you focused (Specific, Measurable, Relevant, Time-bound).

Really?

I’ve always found SMART goals to pale in comparison to creating a vision statement by hand in a journal.

I suggest focusing on a goal that is neither measurable nor time-bound in any traditional sense. Specific and relevant yes, but what the other two terms even mean makes little sense to me.

Think about it:

How can you measure a goal when you don’t know the main points or aspects of a topic you want to learn?

When setting and planning my learning goals, I prefer to avoid reinventing the wheel. I use traditional educational structures instead – very old learning cycles that remove a lot of cognitive load.

I’m talking about traditional semesters used at universities.

See, even though you’re learning on your own doesn’t mean you can’t harness institutional methods for structuring time.

Whether it’s three month or six month learning periods, I suggest you plan your self-study projects within the academic term framework.

I don’t think I’m biased when I make this suggestion, even though my long history as both a student and professor have clearly placed this kind of learning pattern deep in my procedural memory.

The Benefits of Planning Within the Semester Structure, a.k.a. T.E.R.M.S.

Even if I am suffering from a memory bias, the benefits are clear. Planning your goals within a 12-15 week will help you:

- Pace yourself

- Having clearly designated recovery periods will prevent topic exhaustion

- Defined start and end dates make accountability efforts meaningful

- Easier to fit around your regular duties and obligations

- You can better track your progress

- You can batch a small set of subjects together and use chunking while benefitting from interleaving

- Practice using a “Not Now Folder” (more on that in a moment)

Rather than thinking in terms of SMART goals, I’ve replaced this acronym with TERMS:

- Time bound sessions within a clear semester-like period (12-15 weeks)

- Evaluated using a Memory Journal on a daily basis

- Realistic limits based on the specific study load described in the vision statement

- Modular and broken down into specific topics

- Scheduled and fixed study sessions written by hand into a calendar

To give you an example of how I’ve used this technique myself, during the past few years I have researched and drafted a book on Giordano Bruno.

Because this self-learning project isn’t just about the man and his story, I created semesters for myself to cover the books he wrote, but also the topics he himself studied.

For that, I needed to create my own semesters for math, geometry, astronomy, logic and persuasion. I also took deep dives into the books on memory techniques Bruno most admired, such as The Phoenix by Peter of Ravenna.

Without leaning on the established educational structure of the semester, I do not think I would have made nearly as much progress as I have so far.

Two: Reasonable Resource Hunting

We’re all only human. Our brains love to chase shiny new objects.

But when it comes to lifelong learning that will amount to something, you need to let go of the majority of books and courses that will almost certainly provide you with magnificent experiences.

One to five topics max, but usually no more than three. That’s my personal threshold for making sure I’m not spreading myself too thin.

Although pursuing less definitely feels tragic, if you spend all day browsing books, ebooks, free video tutorials and even paid offerings on online course platforms, nothing will get done.

In other words, the fear of missing out is real. But worse is the reality of never getting anything done because you’re constantly spreading yourself too thin.

To keep the amount of distractions to a bare minimum, I suggest that you work primarily with physical books. Find a study place with minimal distractions and use my textbook memorization strategy.

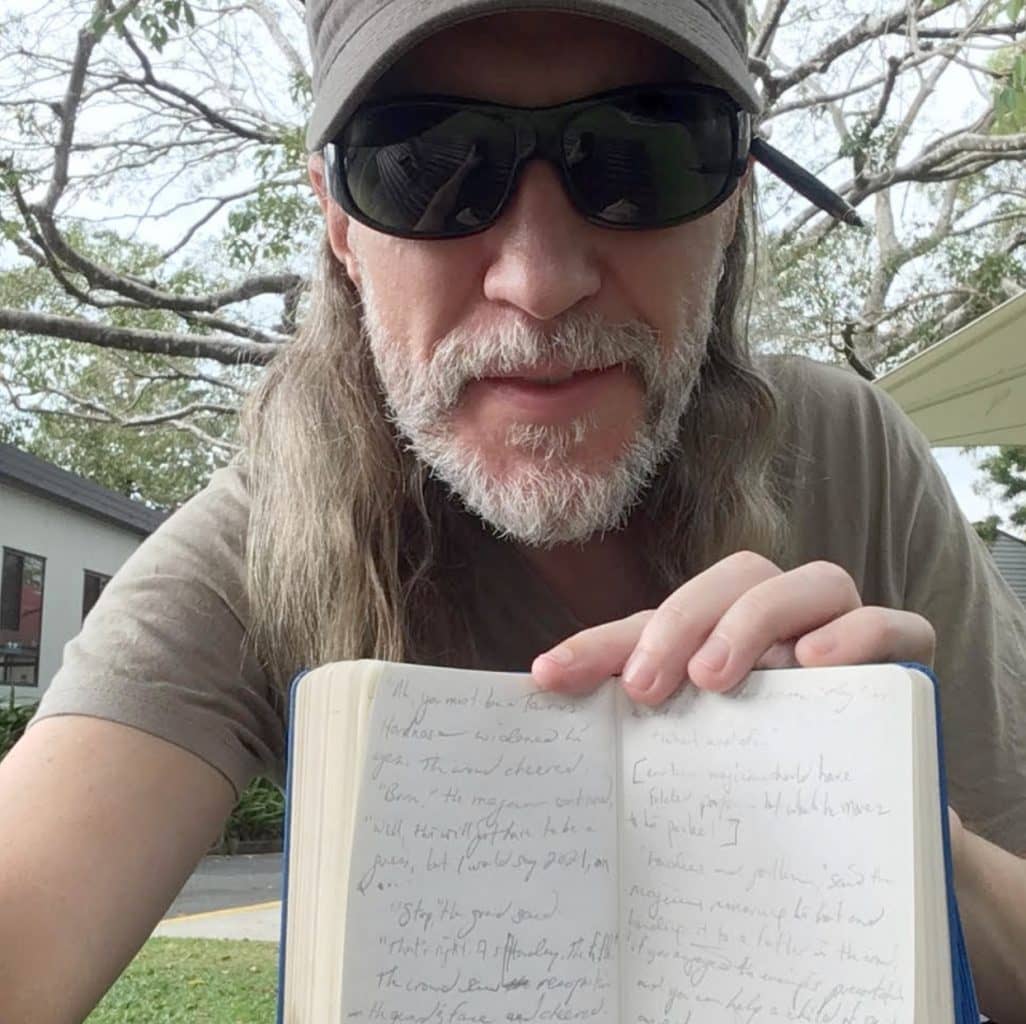

I often read outside and take notes using flashcards that also serve nicely as bookmarks.

When working with online video courses or audiobooks, it’s best to close all tabs and take notes by hand.

To reduce the temptation to research every word or idea I don’t recognize while studying, I like to sit cross-legged on the floor at a distance from the computer.

That way, it’s harder to start consuming another research resource without first completing the current one. Instead, I keep a running set of notes that later serve as a to-do list of all the things I want to look up later.

The Not Now Folder Principle

When I was at York University, I took a fourth year course on Romantic Poetry.

Frankly, the course was bland and I didn’t much like the professor. He went out of his way to be mean to me because I was ill that year and asked for an alternative assignment instead of having to give a presentation.

That drama aside, he shared one strategy that I’ve never forgotten and appreciate so much that he’s entirely forgiven.

He called it the “Not Now Folder.”

Throughout his career, he said he was always distracted by ideas he wanted to research. Eventually, he learned to write them down on slips of paper and then tuck them into a folder.

He said that something curious happened. 99% of the time, items in the “Not Now Folder” because “Not Ever” items.

Scientifically speaking, my professor was helping himself avoid the Zeigarnik Effect. This is the tendency to remember things on your bucket-list, often to the point of distraction.

As a self-learner myself, I can tell you that it’s definitely better not to get yanked around by all kinds of fun and interesting ideas. That’s why I’ve been keeping a Not Now Folder ever since.

This simple place to put all kinds of interesting ideas also helps eliminate the Ovsiankina Effect. This psychological term describes the urge to finish tasks that you’ve started.

A lot of gamification relies on this effect, and it certainly has its positive aspects. But in order to guide yourself toward meaningful progress, you can avoid its negative aspects by only starting projects that fit your vision and follow your T.E.R.M.S.

Three: Use the Best Possible Learning & Spaced Repetition Tools

Whereas I prefer index cards, many people love spaced repetition software programs like Anki.

Ultimately, you need to experiment with a variety of options, from mind mapping to the Leitner System.

The key is being radically honest when exploring various objects and processes that can help you absorb information better.

Memory champions are great people to learn from when it comes to developing total transparency. They love scoring themselves on how much they’ve learned and how fast.

To adopt some of their best techniques for keeping your efforts clear and honest, I recommend learning Johannes Mallow’s journaling method. You’ll have to adapt it to your specific learning goals, but the principles are extremely valuable.

Related to learning tools and processes, you should also consider different types of thinking as powerful assets.

Four: Master Active Learning

Active learning is defined by actively engaging information through:

- Proper note-taking

- Active recall, such as by using memory techniques to aid rehearsal

- The use of active reading strategies

- Analytical thinking and other forms of critical evaluation

- Questioning each and every detail

- Recreating information by mind mapping or writing summaries

- Discussing and debating with others

Each of these activities provide you with the alternative to passive learning.

In other words, you are not highlighting passages in books or downloading someone else’s Anki deck.

Rather, you’re creating your own highly personalized flashcards.

And you’re setting time aside for reflective thinking, one of the most important active learning activities of them all. The trick is to know your personal best time of day for studying so you can maximize the time spent when it comes time to reflect.

Five: Use This Search Hack

When it comes to teaching yourself, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. Even with the best possible resources as we discussed above.

But when you think about it, there are only so many kinds of resources. For example, we’re all limited almost entirely to:

- Books and Ebooks

- Online Courses

- YouTube

- Apps

- Forums

- Friends

- Mentors

To select the best possible material from these content categories, I suggest using search engines a bit differently than you might have considered before.

For example, when I started a self-taught project in the philosophy of metaphysics, I found a fantastic book by searching using this command:

filetype:pdf syllabus metaphysics

That’s all it took for me to find multiple reading lists from top-tier universities.

The next step was simple: order the books assigned by the world’s best professors.

Then, after reading those books, I looked for interviews with the authors of the books I found especially helpful to extend what I’d learned from my reading.

Six: Imagine Challenges & Obstacles Before They Happen

When learning on your own, it’s easy to get discouraged.

I don’t care how much mental strength you have. Learning alone often feels lonely.

It can also feel isolating too. That’s because the more people like you and I commit to memory while so many people in the world fritters their time away on social media, the more alienated we can feel.

One way to balance your learning with well-being is to make sure you imagine all the things that can go wrong. Then, plan for what you’ll do if those things happen.

This technique was popular amongst the Stoics, many of whom were very well-educated people.

In addition to potentially feeling isolated or removed from society, plan for other problems like:

- Topic exhaustion

- Burnout

- Stress and anxiety-induced memory loss

Personally, topic exhaustion has been one of my biggest foes.

To tackle it, I practice a lot of interleaving. This learning strategy involves regularly switching between a small set of topics. It helps keep things fresh.

I also find that in my memorization work, switching from committing one type of content from another helps me remember a lot more without burnout.

Seven: Study Ethically & with Radical Honesty

Self-learning can make it tempting to avoid some of the ethical activities used in traditional learning systems and information sharing.

I’m talking about respecting intellectual property, especially by citing your resources.

That means also making clear when you’ve derived some fact or idea from an AI chatbot.

Why does this matter?

The answer is simple:

To be an intellectual worth your salt, you need to be able to share where your ideas come from so others can evaluate them.

You also need that ability too because things can and do change. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve needed to “fact check” myself when going from memory while writing new books and articles.

Luckily, there are ways to memorize author names and historical dates related to when they released their books.

Although you might think we live in an age of digital content where it’s okay to say, “I can just look it up later,” there are at least two problems with that attitude.

- Due to digital amnesia, people often forget the info that helps them look things up later

- Disruptive technologies have changed search, often to the point of corrupting it almost entirely

Recently, for example, the Internet Archive went down. Its absence made fact-checking myself impossible, though fortunately I remembered enough to continue my personal learning goal.

The point being that you owe it to yourself and others to use memory techniques as much as you can. And cite everything in writing even if you do remember the info so people can assess your references if they’re interested in your conclusions.

Eight: Embrace Failure

So many people email me when teaching themselves the Memory Palace technique with the wish that they “get it right the first time.”

Although their hearts are in the right place, it’s a poor learning strategy.

There are no mistakes when learning. Just results and opportunities to get better results through analysis and repeat attempts.

The more ambitious your learning goals, and the more interdisciplinary they are, the more likely you’ll make what conventional learners call “mistakes.”

But you’re not going to be a conventional learner. You’re going to succeed at this most critical aspect of self-improvement by analyzing what happens and adjusting according to your goals without labelling or judging the outcomes.

How exactly do you embrace failure? As shown on the infographic above, you can:

- Redefine the idea of making “mistakes”

- Use reflective thinking to identify the specific action steps needed for your next attempt

- Stay resilient by continuing to take action and maintaining a positive attitude

- Celebrate effort and recognize the courage it takes to get started learning on your own in the first place

Nine: Be Adaptable

Being adaptable means learning things you’re not necessarily interested in so that your projects can reach completion.

This point is so critical because year after year I see students flounder because they simply prefer to break, rather than bend.

I can relate. And I believe the need for flexibility reveals a “catch” in the meaning of learning on one’s own.

See, although I fully I know from experience and observation of others that it’s possible to teach yourself and learn very fast, there’s a something not quite true about the surface-level image created by the phrase “teach yourself.”

For example, I can fully say that I learned self-publishing on my own. And my first book was a self-published hit long before I started this website.

But I learned a lot from podcasts, business books and courses – all of which involved the efforts of other people.

I also belonged to discussion groups and eventually had mentors I met with regularly.

However, a lot of those beneficial learning activities never happened because I was quite rigid in the beginning. I didn’t want a website, for example.

I also didn’t want to learn how to make videos, skills I needed to keep ahead of the constant change online independent authors and course instructors face.

I found my “inner Bruce Lee,” however. In other words, I remembered his statement to “be water, my friend,” and relaxed my need to do it all my way.

As I discuss in The Victorious Mind, I also followed Tony Buzan‘s advice to follow the rules set by the realities around me. I’m sure glad I did, because otherwise I would have failed long ago due stubbornly refusing to learn skills necessary for my mission.

Ways to Become Flexible as a Lifelong Learner

Being adaptable for you might also involve:

- Leaving behind an all-or-nothing attitude and learning incrementally

- Seeking situations outside of your comfort zone so you can learn in real-life scenarios

- Developing a growth mindset and facing any fears you have around change

- Embracing ambiguity or comfort with not always having all the answers

- Adapt to learning when you face limitations in time, money or access to resources

- Cultivating intellectual humility so you can admit when your knowledge is incorrect or needs updating

Becoming an adaptable learner isn’t necessarily easy. But it’s the most important skill of all apart from developing a strong memory in my view.

Related Posts

- Stoic Secrets For Using Memory Techniques With Language Learning

Christopher Huff shares his Stoic secrets for using memory techniques when learning a language. You'll…

- The German Professor Who Defends Memory Techniques for Language Learning

This professor defends memorization techniques for learning foreign languages and has the science to prove…

- Memory Techniques For Chinese with Mandarin Blueprint

Mandarin Blueprint provides exceptional material for learning Chinese, including characters, pronunciation and the best memory…