A few years back, I walked out on the TEDx stage, opened my mouth, and for 13 minutes and 22 seconds, a bunch of words spilled out of my mouth.

A few years back, I walked out on the TEDx stage, opened my mouth, and for 13 minutes and 22 seconds, a bunch of words spilled out of my mouth.

The sentences and quotes flowed easily, without my having to think about a single one of them.

At the end, a bunch of people clapped. I said goodbye to the people I’d met (by name, of course, because I’d memorized them), and then went home.

But wait. Isn’t this post about memory strategies? What does giving a speech have to do with strategies to improve memory?

That’s the beauty of what happened that day on stage. Because I have a number of memory strategies, it was easy for me to give that speech.

I can think back to a number of public speaking engagements that were stress-free, totally blissful, and perfectly wonderful — all because I have (and use) memory strategies.

This isn’t to say that stress-free means problem-free.

Far from it. As you can see in this video of the TEDx Talk, people laughed at something I wasn’t expecting…

…but thankfully, I was able to get back on track by simply falling back on the strategies you’re about to learn.

When I think back on all the times I’ve walked into a room and remembered the names of people and been able to speak to them without notes, I’m continually grateful for these strategies.

It makes me sad how many people suffer badly in life because they don’t have a strategy. That’s why today’s post will cover how to develop and cultivate a memory strategy that helps you with memory improvement.

Ready to bring memory strategies into your life?

Here’s what this post will cover:

Memory Strategies to Boost Retention and Recall

1. Pick a Long-Term Learning Project

2. Structure and Organize

3. Break It Down

4. Schedule Everything

5. Make Relationships

6. Make Mind Maps

7. Use Priming to Form Mental Models

8. Create a Memento Mori

9. Optimize Your Lifestyle

Before we dive into the strategies themselves, let’s look at what a memory strategy is, and why it’s so important to develop one.

Memory Strategies to Boost Long-Term Memory and Recall

Each of the 12 strategies below can be used separately to aid in improving long-term memory and memory recall. But the strategies become even more powerful when implemented together.

Let’s look at each memory strategy in detail.

1. Pick a Long-Term Learning Project

This first strategy is deceptively simple: have a long-term learning project to help you focus your attention.

You might decide to have multiple projects, but I like the discipline involved in focusing on a singular project.

That being said, I currently have several long-term learning projects that are all intertwined. My current project is a very elaborate and deep project I’ve been working on for years, called The Art of Memory.

As another example, if you are a medical student you could turn your learning into a longer-term project than you originally anticipated. To become the best possible doctor, you could learn more about the history of medicine. You might choose to create a long-term learning project around medicine during the Italian Renaissance.

Every time you learn more, find the clues that lead you to your long-term learning project. Build out a concrete set of things to study – planned out over time – that will help you create a foundation for connections in your neuronal networks.

Each new book you explore or subtopic you examine will create more and more connections.

What this type of long-term learning helps you do is learn how to focus. You’ll extend your concentration on something called cognitive shifting.

Please note, we’re not talking about multitasking or task switching here. Instead, cognitive switching is the ability to very consciously switch gears in a way that doesn’t disrupt your focus. It doesn’t incur a mental cost; in fact, it creates more energy than it burns.

In order to be at the top of your memory game, you need to master cognitive switching. You need to be able to switch gears on a dime, all the while maintaining your focus on being the best possible learner. This simple aspect of how memory works is the key to concentrating while studying.

Your long-term learning projects will teach you to master this type of focus, to juggle multiple threads of thoughts and ideas at a time. And over time, you’ll develop memory reserve (sometimes called cognitive reserve), which leads to long-term fortification of the brain against damage.

Exercise: Pick one life-long learning project

It might feel too limiting to pick just one project, but trust me. You can start with just one, and if you spend a few months focused on the single project and feel like it’s too limiting, you can add more in.

If you have trouble with the idea of picking just one thing, I recommend watching (and taking action on) my Memory Training Vision Statement video.

My Art of Memory project leaves me swamped in variety. My head spins every day as I make my way through page after page, exercise after exercise. I just keep following the adventure and haven’t found an end yet!

Whatever you choose, be the brave warrior of the mind who is courageous enough to zero in on one thing and be satisfied with the totality of what you get. Instead of trying to “have it all” and ending up with nothing, see how it feels to commit to a singular path for a while.

2. Structure and Organize

The most helpful thing you can do to improve memory is to be a “self-organizing structurer” — become someone interested in structuring things. One of the top ways to do this is to learn about bibliography.

Just think: what if you could structure your mind to store information like a library?

Imagine if you committed the Dewey Decimal System to memory. You would have a never-ending Memory Palace where you could store every piece of information you wanted!

But for those who don’t want to put in the effort to memorize something as extensive as the Dewey Decimal System, you can still think bibliographically. It’s simply a major tool of structure and organization.

To understand how libraries came to be structured as they are just might influence you to begin structuring your mind in a similar way. If you’re already familiar with Memory Palaces, you’ll see they are structured both thematically and bibliographically.

To tackle this style of self-organization, have several styles of note-taking at your disposal. Two helpful resources here on Magnetic Memory Method are the note-taking YouTube video below and the post about How to Memorize a Textbook.

As I discuss in How to Memorize a Textbook, index cards can be a helpful tool. Rather than taking notes out of a book in a linear fashion, using index cards makes them moveable.

When you get ready to memorize the information on the cards, you can mix and match the cards, move them around, and memorize the information in the order it makes sense. Instead of being locked in the same linear mode of the book itself, you can be flexible in your learning and memorization.

As you structure and organize your thoughts and memorization, try to maintain what I call an “index flex” that allows you some kind of structure that you can also move around and restructure as needed.

When you have your structure and organization in place, you’re able to use your memory tools in a way that’s streamlined and strategic.

Exercise: Read a book using the How to Memorize a Textbook methodology

This exercise is as simple as it sounds. Choose a book to read – any book – and apply the 10-step checklist in the How to Memorize a Textbook video (or blog post, linked above).

3. Break It Down

At some level, this means chunking — breaking information down into smaller more manageable chunks, or grouping information into units.

For example, instead of listing a phone number as 9872380341, it’s easier to read when written as 987-238-0341.

For those interested in taking this a step further, you can also add chunking to mnemonics using things like a PAO, 00-99, or Dominic System.

There are many different approaches to applying this chunking method. You could try dedicated practice (a musical concept applied to memorizing a phrase) and break down a larger phrase of a foreign language — maybe taking it a word or two at a time before bringing the entire phrase back together.

This is a very important strategy in and of itself, but when you add mnemonics inside of a memory strategy it takes on its own dimension:

First you divide and then you encode. Then you can break each part down, loop it over and over, and make the process incredibly simple.

Exercise: Use notes you’ve gathered and “chunk” them

Take a section of notes you’ve written out for school or work and chunk them down. You can even use the notes you took when you followed the How to Memorize a Textbook method in the last section.

Take your index cards, recombine them, chunk them, make them meaningful and useful, put them into a Memory Palace, and then use the dedicated practice strategy above.

Timo Hahn, on my testimonials page, shows how he uses this approach in both learning and with his consulting clients. He uses this strategy with index cards (the index flex) and chunks it in different ways to improve how he serves his clients.

4. Schedule Everything

Scheduling is the antidote to cramming.

When I was preparing to do my TEDx talk, I had to schedule very carefully. I had a ton of things going on at the same time, and it would have been a terrible idea to cram all my preparation into the night before.

I even scrapped my speech and did a completely different talk than the one I originally planned — the only way I could have accomplished that was to schedule ahead and have enough time to memorize not one, but two, speeches!

This comes down to an 80/20 rule. When you pick up the book you chose in the second section of this post, you’ll decide on a certain percentage of other books to read afterward. (The debt obviously grows over time, but you don’t have to read everything.)

Schedule carefully, and you’ll fit in much more learning and growth in the long-term. On the flip side, if you don’t schedule you’re not likely to get much done.

For example, to combine scheduling and chunking, go through the citations at the end of your book and choose three other books. Go to the library (or your library’s online book lending portal) and at least look at them. Skim them or use priming to go through them.

It’s a form of chunking, so to speak: “Out of this bibliography, three books. I’ve looked over these 3, perhaps held them in my hands, flipped through the pages, and understood that I want to read chapter 4 of one of them.” Then schedule when you’ll read chapter four.

If you try this without a long-term learning project in mind to guide and govern your exploration, you’ll end up with all these shiny new books and no plan to actually make use of them.

Remember, it’s not about having it all — instead, it’s about having clarity on specific goals, and in a way that honors the nature of how time works.

Next, divide planning and organizing from reading and remembering.

There’s the reading part, when you use some sort of device to capture what it is you want to memorize. And there’s the remembering process, when you’ll commit the things you captured to memory.

Also schedule self-testing. First ask, “what do I want out of life (or this learning project)?” Then make it happen, schedule self-testing, and schedule some journaling.

Why? To test that you really want the thing you think you do.

When self-testing, set time to:

- Look through and ask questions about your notes,

- Write a summary of what you’re doing, and

- Make sure you really understand the topic.

If you self-test and realize you’re not quite ready, you can go and look at another book. The testing process will help you identify where your weak links are and how to fix them.

Exercise: Organize and schedule your reading list

Remember, organization and scheduling go together! For this exercise, organize your reading list, and then schedule time for reading, reflecting, and self-testing.

If you follow this set of steps and turn it into a regular practice, you will have an amazing memory as you get older. Now is the time to get started, no matter what condition you’re in at the moment.

Start to read properly. Start to schedule time properly. Progress toward getting better and better at both. Practice the things you really want to get out of life. And you’ll be so amazed by how many incredible things start to happen.

5. Make Relationships

Make relationships — both to people and to existing memories.

If you’re in a particular situation and you hear someone say something, what existing memory surfaces? If you think of an author or a book or an object, what comes up?

For example, if I think of Frances Yates, the memory that surfaces is the first time I read The Art of Memory. Reading Moonwalking with Einstein also comes up, as well as the magic shop in Toronto where I think I saw Jay Sankey one time.

These are all slightly random examples, but they demonstrate how to practice linking a thing to existing memories.

It’s the practice of being able to come up with a memory (or more) on demand and make a relationship to it, even if it’s a very loose relationship. It’s also the practice of fluid memory and free association. And the more you can do that while you’re reading and learning, the more you’ll remember.

Next, practice making analogies. Even if they’re incorrect, or terrible, they help you make mental relationships between two things.

It also helps to compare and contrast the two things. Contrasts are often more useful, simply because existing memories and analogies are more like comparisons. So balance out the focus by using more contrasts.

And finally, understand what facts really are. Don’t be lax and let yourself think they’re what you want them to be or what you were taught in school. Instead, seek the real truth about what facts are. They’re usually heavily contingent and testable.

Set yourself up to rock and roll on that higher factual basis, as opposed to getting stuck in the weeds or the gears of the machine — the things that lead to all sorts of nonsense on the internet and in journalism.

Exercise: Think of an analogy to memory strategy

Think, “What is analogous to a memory strategy?” First, make an analogy, and then think about what the contrast would be to that memory strategy. Try to write down at least five analogies and their contrasts.

And then ask yourself, “What is the factuality of memory strategies?” Write down the answers you discover.

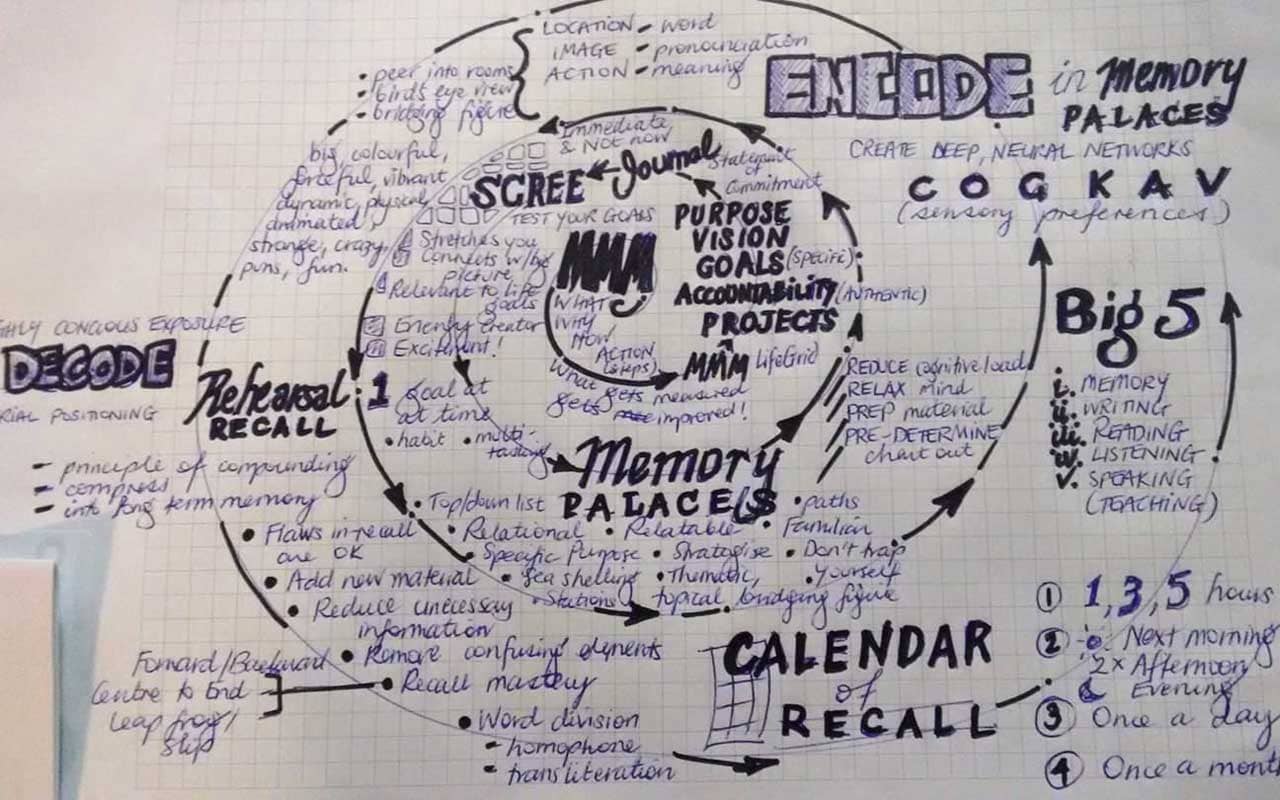

6. Make Mind Maps

This strategy is wonderful, extraordinary, and perhaps even unparalleled.

Mind mapping is about thinking and remembering. It also lets you make analogies and stress-test factuality, as well as do contrasting and comparison. It enables you to break things down and do chunking in a certain way.

But even better, you’re not beholden to all those things. It comes down to, “What is your strategy?”

When you take your long-term learning goal and think of your strategies within it, mind mapping will have a place. And how, specifically, you use mind mapping will also have a place.

There are many different styles of mind mapping.

One mind map style is how Ke Ko took what I said about sea-shelling in Memory Palaces and applied it to her mind map. This is like the Magnetic Memory Method in a nutshell. So beautiful.

Mind mapping can also be useful for spaced repetition.

For example, let’s say you mind map something you want to memorize. You now have this wonderful visual display you can visit and revisit as often as you’d like — and I would recommend keeping track of how many times you revisit it by putting a small roman numeral in the bottom corner.

Aim for at least 10 reviews and you will see great benefit. This is a creative use of spaced repetition. It’s not mnemonics or a memory technique (at least in the sense of Memory Palaces), but it’s a great way to combine mind mapping and spaced repetition.

You can also use a mind map as a Memory Palace. To learn more about mind mapping, watch our YouTube playlist covering Mind Map Examples.

Exercise: Use 3 styles of mind mapping on your life-long learning project

Take your life-long learning project and mind map it using at least 3 different mind mapping techniques.

If you’re not familiar with all of the styles of mind mapping, I recommend Tony Buzan’s book Mind Map Mastery to help you choose. The book also has a delightful resources section that will help you expand your learning project.

7. Use Priming to Form Mental Models

When you hear the word “priming” you might immediately think of the speed reading technique.

But that’s not the only thing we’re looking at in this context — there are also other types of priming. In the priming world, speed reading is essentially biography, but it’s also observing mental responses to difficulty and then strategizing based on your observations.

Here’s one approach to self-priming: instead of saying, “Oh, this is so difficult. Poor me!” you can say, “Yeah, this is difficult. But I can do it.”

For example, in the coaching world, there is research that indicates certain athletes have different motivational types than others. There are some who need to be told, “This is going to hurt.” Somehow, bracing for the inevitable pain improves their performance.

And I personally have a fighter pilot mentality: “Come on. Let’s go! This is a war, and we’re gonna win.” Maybe I played GI Joe too much when I was a kid.

Many of these mental models are formed in childhood, and a lot of it is positive. Much of it can be tapped to improve your performance.

So the key here is to understand what your motivational model is. Observe your own mental responses to difficulty, and then use that information to strategize and turn the wind in your favor.

In the book, he lays out why and how to explicitly and expressly put time aside to figure out your mental models and create some secular rituals around it. Then be prepared to explore, challenge, and change them as you learn what works for you.

One secular ritual you might choose to explore is memorizing playing cards. I personally like to memorize 13 cards at a time, but you can start with whatever number you like.

In creativity studies, there’s also a type of priming — and one priming creativity exercise is to do a small and quick creative burst of exercise to warm up your brain before you tackle the task at hand.

Or if you’re preparing to memorize something for a test at school or for your language learning, before you jump into the challenging goal, do a quick exercise to warm up (much like an athlete warms up their muscles). Then be sure to cool down and relax.

Exercise: Pick a mental model

For this memory strategy, choose a mental model, build a secular ritual that works for you, and learn the best way to prime yourself.

8. Create a Memento Mori

A Memento Mori is something that reminds you that you are eventually going to die.

It may sound morbid, but we don’t get to choose when or where or how it’s going to happen. This is why now is the best time to try the things you’ve always wanted and to get involved in improving your memory.

For example, Mr. Death is always on my desk. When I was in my band I always had him on my bass strap, reminding me he would “catch me later.”

This shouldn’t terrify you or haunt you. It should be a comfort because as I interpret the great Giordano Bruno, there is no death, and there never could or can be — but, nonetheless, that thing you think you are, that “I”, that ego, you think it’s going to die, and that causes so much pain.

Instead, use the reminder that life is short to do the things you’ve put off. Seize the day. Live the life you dream of.

Another Memento Mori is the amor fati coin, which says, “Not merely to bear what is necessary, but love it,” which is a quote from Nietzsche. His internal Memento Mori is known as the myth of the eternal return — imagine what it would be like to wake up and live the same day, every day, for all of eternity.

How would you live that day? What would you do to make sure it was not merely tolerable, but the most wonderful day possible?

Say yes to life. Instead of getting stuck in “poor me” mode, take the opportunity to make whatever changes are possible in your life.

Exercise: Create your Memento Mori

Choose a symbol or reminder that life is short. Whatever you choose should motivate you to make the most of every given day.

If you’re having a hard time choosing, Richard Wiseman’s book 59 Seconds has a wonderful funeral exercise that can help.

9. Optimize Your Lifestyle

This strategy is fairly simple, but it’s also a very important part of your overall strategy.

In a nutshell:

- Get enough quality sleep

- Exercise and move your body regularly

- Eat a healthy diet and stay well hydrated

- Have a plan to manage the daily stresses of life

- Sit for daily memory-based meditation

If you’re not sleeping properly or working on optimizing and maximizing your sleep, you’re missing out. Your brain (and memory) are dependent on getting a good night’s sleep. The explosive, blissful feeling that comes from being reliably well-rested is some sweet stuff.

Exercise is also essential. Socrates even said, “it is a disgrace to grow old through sheer carelessness before seeing what manner of man you may become by developing your bodily strength and beauty to their highest limit.”

You owe it to yourself to be at the height of your athleticism and try to hold onto it for as long as you can.

Another life management tip that is great for your memory – but very rarely discussed – is to have an emergency plan for your family. Having this plan in place takes weight off your shoulders and frees up your mind to think about other things.

For your plan:

- Create and sign a will

- Designate an emergency meeting point

- Have fire blankets and fire extinguishers handy

- Store enough food and water for 2 weeks

- Have a reasonable stock of toilet paper

In his book Into the Magic Shop: A Neurosurgeon’s Quest to Discover the Mysteries of the Brain and the Secrets of the Heart, James Doty talks about many of these things. He also talks about the dark side of meditation and mindfulness — where you not only get distance and discernment, but you also get detachment and you’re not so concerned about things.

You’re able to let go of outcomes, and might even get to the point where you exploit people and situations because of it. So make sure you have a good moral compass as you make meditation part of your lifestyle.

Exercise: Audit your lifestyle categories and make a plan to improve them

For this strategy, audit every lifestyle category above. Make a plan for how you want to improve in each category, and then schedule the improvements in.

Do your research using all the tools we’ve talked about as part of your life-long learning project. And then remember every step you take helps to improve the health of both your body and your mind.

Exercise: Learn the Magnetic Memory Method

There are a number of ways to learn the methods, strategies, and techniques in the Magnetic Memory Method. But the easiest way to just get started. For that, I suggest the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass.

Memory Strategies for the Long and Short-Term Memory

You now have 12 different strategies at hand you can use to improve memory and take on the world. You have your chosen mental model. And you know what kind of person you want your memory studies to help you become.

Now it’s time to take these strategies and start forming habits. Show up long enough and consistently enough. Do the work. Then come back tomorrow and do it again.

Remember, memory is the ability to recall things on demand because you’ve been able to store them — and strategy is the science and the art of accomplishing goals.

To help you accomplish your goals through memory strategy, sign up for your free memory improvement course today. And remember the speed of implementation rule — don’t just sign up. Get started right away. Here’s where to go if you’re interested:

Related Posts

- Memory Improvement Techniques For Kids

You're never too young to get started with memory techniques

- How to Improve Short Term Memory: 7 Easy Steps

Many people think you cannot improve short term memory. In truth, you can. Enjoy these…

- 3 Blazing Fast Ways To Increase Memory Retention

Memory retention... what the heck is it? Is it worth worrying about? If so, can…