Is there a difference between logical and rational thinking?

Is there a difference between logical and rational thinking?

Yes.

And one problem even worse than not knowing the difference is this:

People often use logical thinking when they should use rational thinking and vice versa.

I have this issue with a friend of mine all the time who treats logical thinking almost as if it is a religion.

We’ll use a recent discussion he and I had as an example.

In our argument, he used what he considers to be logic in a way that led him into a major inference from partial data fallacy. He also neglected the importance of small examples.

Don’t worry. I made logical errors too, oversimplification in particular.

To help make sure you’re logical when you want to be logical and rational when you want to be rational, let’s dive in.

Logical vs Rational Thinking: The Simple Difference

As I mentioned, the problem we face is that difference rationality vs. reasoning is not clear because people use these terms in all kinds of ways.

But let’s do our best to nail down some clear and distinct definitions as we strive to improve our critical thinking skills.

Logical Thinking

At the simplest level, Graham Priest describes logic very well:

“Logic is about validity – what follows from what, and why.”

Strictly speaking, people using logic construct syllogisms. There are at least three kinds of syllogism:

- Conditional Syllogism: If A is true then B is true (If A then B).

- Categorical Syllogism: If A is in C then B is in C.

- Disjunctive Syllogism: If A is true, then B is false (A or B).

Rational Thinking

Reason, on the other hand, is typically about showing the basis for causes, beliefs, actions, events and facts.

Let’s take this one step further:

To reason something out is generally considered an act of applying logic to find explanations that make sense.

The problem is that many people reason things out without using logic. We bring in experience, context, emotions, personal values, convictions, ethics and other things that make us human.

Think about the last time you had an argument. Did the person you were arguing with draw out a mathematical “if this then that” argument map as part of the critical thinking exercise?

Probably not. Chances are they tried to reason things about with more tools than just syllogisms. It’s very difficult for even the most logical people not to do so. But when they cannot reason, whatever they are trying to communicate often fails.

Example

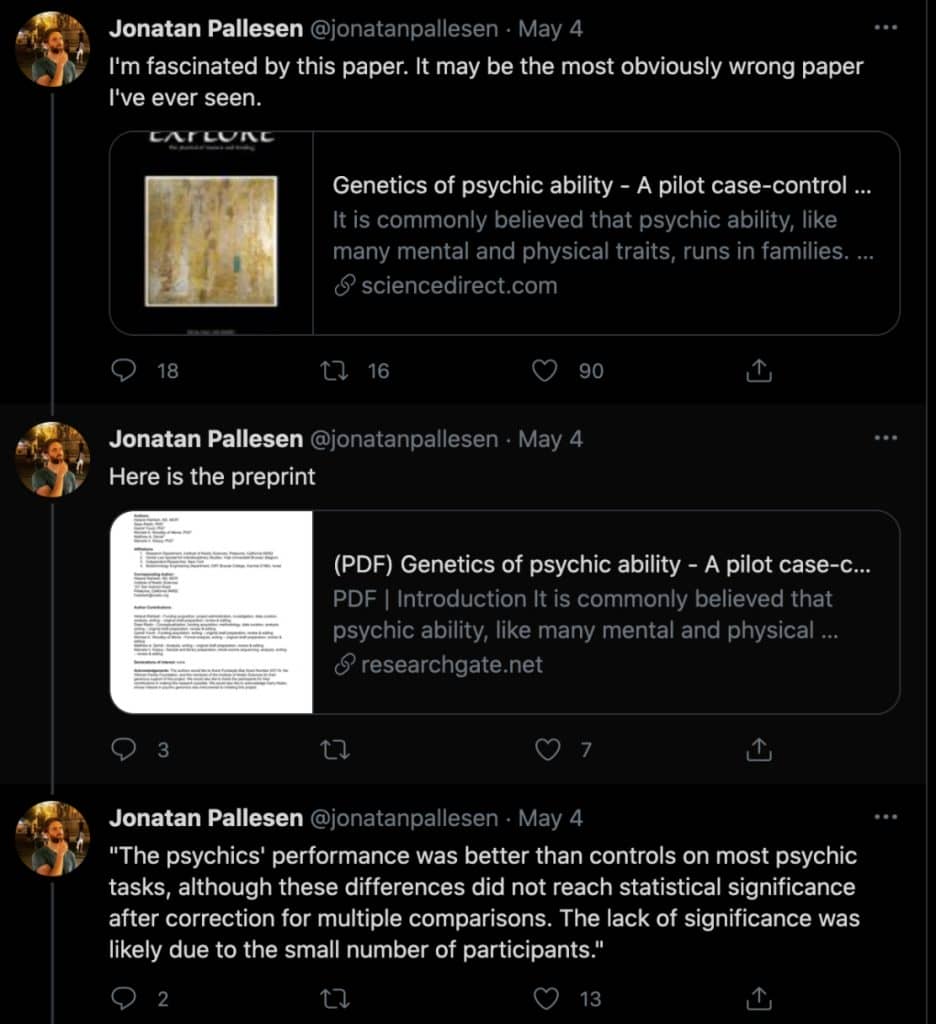

After learning from Jonatan Pallesen about how a major science journal had published a clearly pseudo scientific paper about the “genetics of psychic abilities,” I sent the paper to a friend.

I hadn’t seen anything this bizarre since The Mandela Effect went viral, and thought about my friend because we have a long-standing disagreement about the health of peer review in the academic world.

Admittedly I started the argument off with a dramatic oversimplification that attacked his views:

“Still believe in peer review? More evidence it is dead.”

Defending Absurdity

My friend responded:

“Cases of such papers being published are much more common. Not news. After peer reviews they get unpublished. Note: I haven’t read this paper, only the title and abstract.

But sometimes they don’t get unpublished. Yet again, almost no harm done. The system is self cleaning.”

“Almost” no harm done? How can someone judge that after admitting the example went unread? In reality, people are bilked of millions of dollars per year by psychics. Having charlatanism validated by a scientific journal, however briefly, shows that there are deep issues that increase harm that already exists.

Irrelevant Logic Enters The Picture

I’ll spare you the entire exchange, but my friend was using logic and later pulled out one of those syllogisms we talked about above:

“A – subset or idiotic papers published, A is a part of B – all scientific community, conclusion B cannot be trusted.”

The problem is this:

I never talked about “science,” nor did I say that it cannot be trusted. Science is a tool used by humans, and there is nothing about it anyone (or anything) has to trust.

Further, I’m aware of my emotions around it. Many people say that emotions should be excluded from rational thinking, but isn’t that irrational? Wouldn’t you want to include what might actually be valuably rational in the emotions?

There’s no easy answer here, but Aquinas had some suggestions about how to act prudently that are worth thinking through in this regard. Some people will reject considerations from the level of n=1 personal experience, but when it comes to memory science, Luria’s study of Shereshevsky has been praised for making sure to bring individual experience into his object analysis.

Rational Thinking Requires Broad Evaluation

Again, my friend admitted he hadn’t actually read the paper. What’s the use of applying logical thinking to dismiss something you haven’t read? Rational thinking, which tries to find the basis for why something is bad, requires evaluation.

This means that even if my friend’s syllogism is well-formed and sound, it is irrelevant as a rebuttal. It’s also important to question why he neglected to read the article yet still felt able to evaluate it on a purely axiomatic basis.

Here’s more nuance on why this is so critical:

My friend was using logic in a context where it has limited use because the statement required reason to find the basis of why something is happening. Instead, he gave a syllogism to demonstrate how I was wrong about something I did not actually say.

Now, it is a problem that I used the word “dead” as shorthand for the problems with peer review I was citing. I also have the problem of assuming he remembers more about previous conversations on the topic.

If I remember these things any better, it’s only because I use the memory skills I offer you in this course:

And to be fair, there’s a lot to remember about our exchanges.

Almost all of them include lots of “link chess” back and forth as we trade evidence.

Sadly though, my friend has the habit of commenting without reading. Instead of sending back, “I don’t have time to read this right now,” he sends his opinions. When I rebut those opinions, he sends logical syllogisms back instead of reasoning through whatever I’m talking about.

“Link Chess” Pays Off Only If You’re Reasonable

He did send me a good link though, one from Science about a “cleansing” experiment in publishing (but not “self cleansing”) had revealed. I took the time to read it before formulating a view.

In other words, I tried to reason out why he thought this study supported his dismissal.

But as good as this study is, it is about after the fact issues in publishing. It relates only tangentially to an incredibly puzzling example of a publication that may have gotten through for reasons one would hope to expose (if they’re there). Yet, my attempts to reason through why such articles get published in the first place went unheard, and I can only take responsibility for how I framed the discussion in the first place.

What I wasn’t going to do was send a syllogism in return, because logical thinking was simply not appropriate to the context.

One more point:

My friend’s inference from partial data shows the risk of throwing out logic, especially when you admit that you haven’t even read the material in question. My mistake shows the risks incurred by some issues we’ll talk about next.

How To Balance Reason And Logic

We all make mistakes.

In Paradox Lost: Logical Solutions to Ten Puzzles of Philosophy, Michael Huemer suggests a number of critical thinking errors we tend to make. I’ve already listed some of them. Here are a few more to extend today’s example:

Assumptions

I made the error of thinking my friend would treat the word “dead” with more nuance than he did. As a result, I seem to have triggered what I find to be a preachy logical response with no reasoning whatsoever.

Neglect of the small

My friend often likes to refer to slippery slope fallacy whenever I show concern about problems in the scholarly world.

The problem is that there are at least six different kinds of slippery slope fallacy. Not only that, the world does have slopes and some of them are slippery.

To ignore incidents like the kind I sent to my friend and write them off as isolated poses some potentially huge problems. As Huemer points out, “We tend to confuse indistinguishability with qualitative identity. This last mistake is aided by a tendency to confuse what is true with what can be verified.”

In reality, we can verify the truth of many problems with peer review and they have led to some massive consequences. Things have grown so contested that esteemed philosopher Peter Singer and some colleagues have felt the need to found the Journal of Controversial Ideas so that people can publish without being excluded by biased editors or social media reprimand.

Confusion

The confusion in our example was started by me because I used the word “dead.” I could have been more precise or at least more nuanced. I was also playing link chess out of the blue to reengage an earlier conversation.

Binary thinking

My friend was defending science at large – something I would generally applaud.

The problem is that peer review is not science. Peer review is governed by impassioned human beings and is subject to corruption and decay. It is also not “self cleaning” because peer review is not a god in the sky. It is something that humans collaborate on, and they need to do so with both logical and rational thinking in order for it to operate in a fruitful manner.

But my friend was so stuck on using logic that we have yet to come to consensus on a problem his own language acknowledges. After all, he used the term “idiotic papers” in his own syllogism.

I did not say that all such papers should not be published. I was only asking for his consideration of one paper in particular. Again, I admit that I didn’t ask for that consideration in a very good way. But I can only take so much responsibility for how he fell into one side of a binary – the one he prefers instead of the one our world desperately needs at the moment if science is going to function as well as it could.

If you want to balance reasoning and logical thinking in your life, I suggest diving deep into some critical thinking strategies. You’ll also want to read as many critical thinking books as you can.

Because in reality, both logical thinking and rational thinking are needed. Otherwise, it’s pretty easy to see that even logical people can wind up using logic in some pretty irrational ways.

Related Posts

- The 10 Main Types Of Thinking (And How To Use Them Better)

If you need to learn the main types of thinking with specific and concrete examples,…

- 5 Critical Thinking Quotes That Will Instantly Sharpen Your Mind

Most critical thinking quotes have nothing to do with the critical part. These 5 quotes…

- 9 Deadly Critical Thinking Barriers (And How to Eliminate Them)

Most barriers to critical to critical thinking are easily removed. Read this post to boost…

4 Responses

The difference between logic and reason (rational thinking) is something I’ve been pondering too. Simply put, logic is the inferences that follow from certain premises, as you outline at the start.

Reason is a broader concept, requiring logic, but also trying to ensure the premise is founded on something real to begin with (consistent with observation or already verified inferences); and then checking your conclusion at the end is also consistent with observed reality and experience. Reason requires logic, but requires a broader perspective compared to just logic.

You identify the first part of what logic is correctly at the start, but then you seem to go off the rails somewhat in the rest of your analysis. In particular associating non-objective feelings with ‘reasoning’.

I would obviously need to see the whole exchange to be sure, but my first impression is that your friend was taking the broader view required to be rational, you were taking the narrower view, and you’re perhaps projecting. You were drawing his attention to a particular instance where peer review had led to an irrational conclusion, and you were correct. But you then generalised that to state that ‘peer review is dead’ – in other words worthless. He was taking the broader view that although a barrel of good apples may have the bad one in it, it doesn’t mean the whole barrel is worthless and in fact most of the apples are good.

Thanks for your post.

Perhaps I was not clear enough in describing this particular example from the past, but I hoped to point out that there are issues in taking the broader view – especially in cases where people like my friend was willing to comment on an article he had not read. That behavior may have many reasons, and I suggested interrogating what those reasons might be.

To some of your other points, I’m not certain that reason requires logic, and if it does, it’s not clear which one. There is more than one kind of logic, and on this memory blog, at least two are regularly deployed. One of them is essential to the history of memory techniques and useful to consider in the larger context of this project (links are given for fuller context in the post).

It’s not clear to me that there is such a thing as “non-objective feeling.” It seems to boil down to cognitive awareness of how emotions appear to the individual in a complex web of relations. And according to both standard and non-classical logics, pretty much everything is an object with respect to the consciousness in which it appears.

For this reason, I’m not sure I went off the rails at all, nor am I sure what it would mean to do so. There are certainly Bayesian issues that challenge some of what I’m saying, but again, I link out to contextual considerations that are specific to this blog and the memory issues addressed here.

One might also consider this post not as some be-all/end-all pronouncement, but a matter of discourse. So I thank you again for your post.

I can’t believe you wrote this yesterday. And I deeply appreciated your story and your break down of understanding. I’ve thought about both logic and practical for a long time being a fine artist myself, and these words/concepts have always made me create.

Currently, I’m going through my longest relationship breakup… and with that I (obviously) have to dive deeper to understand and contemplate everything. I love him, always will, but he kept insinuating logical reasons to fault on me that the relationship went south. I’ve always perceived myself as a rational person and don’t want to give up my hope. So I thank you for writing this. It gave me another sense of security that emotions are valid, there is a difference between logic vs practicality, and not everything can be perfectly defined; but when someone else can be pondering the same notions as you are, it’s the most comforting of all.

Thanks for your post, Claire.

Some people think emotions have a logic of their own, and there is merit to the notion. It’s well worth exploring.

“Logic” might not be the word that a lot of people want to accept when it comes to the cause and effect operations of how some emotions play out, but it is surely illogical to deny the value of inquiring into it.