I absolutely love the Ovsiankina Effect.

I absolutely love the Ovsiankina Effect.

That might sound a bit strange, but understanding the psychology of unfinished tasks has helped me get more done than I ever imagined possible for the past two decades.

I’m not just talking about the hundreds of articles I’ve written for this blog, or all the videos and podcasts.

I first discovered the power of approaching unfinished tasks in a particular way when I was in university.

Thinking about it properly helped me have so much time-freedom that I wrote three novels when I was in university. I also played in bands, worked at the legendary Queen Video in Toronto and participated in many fun cultural events.

I still use my understanding of the Ovsiankina effect to maintain maximum productivity to this day.

And on this page, I’ll share with you what the effect is and how you can easily use it as a super power yourself.

Ready?

Let’s dive in.

The Ovsiankina Effect Defined

If you’ve ever felt that urgent need to finish something you’ve started, that’s the Ovsiankina Effect.

The effect is named after Maria Ovsiankina, a psychologist who was fascinated by the closely-related Zeigarnik Effect.

Whereas the Zeigarnik Effect suggests that people tend to remember items on their to-do list, often in a way that causes stress, the Ovsiankina Effect shows that people only tend to enjoy peace of mind after items are completed.

As one study has shown, one reason people choose to work evenings and on weekends boils down to psychological relief. It feels better to be getting something scratched off the to-do list than it does to think about them. As the Zeigarnik Effect shows, unfinished tasks are highly likely to keep arising in the mind.

Personally, I’ve always found unfinished tasks challenging. That’s why I’ve learned to use both of these effects as a core driver of my success.

How I Learned To Beat Both Effects And Leverage Their Power

Some researchers now call these two effects “Interruption Science.”

That sounds to me like an appropriate name for the Zeigarnik and Ovsiankina effects because when I was in university, the mental interruptions stressed me out to the point of illness.

In 1997, I was paying my way through university by working in a paint warehouse almost an hour by bus from York’s Keele campus in Toronto. I was so worried about my assignment deadlines and filled with craving to work on them that I often made expensive mistakes. I often crashed my Pallet Jack while loading trucks, leading to wasted product and time lost to cleaning up a lot of messes.

Worse, when I did have time to study, I was horribly disorganized. I had no idea about interleaving or what would eventually serve as my textbook memorization strategy.

Lacking any kind of coping strategy, I quit both school and work for almost a year. Later, I also had to leave university due to mental health issues. I tell the whole story in The Victorious Mind.

When I finally got the courage to go back to school and work, something dawned on me when I was at the registrar’s office:

If I could get my course syllabi early enough, I could start completing my reading and writing assignments early. That way, I would be much less stressed out while at work.

The technique succeeded and improved my life across the board.

Why The Psychology of Unfinished Tasks Harms Some Of Us

There are several reasons you might struggle with these effects.

Let’s have a look at the biggest of the bunch.

Shouldism

I met a lot of people who didn’t seem to care at all about their assignment deadlines during my studies. Or if they did, it was barely visible to me. Another explanation might be what scientists call the Hemingway Effect, which shows that some people benefit from failing to complete tasks.

Dr. Marina Milyavskaya has suggested that many of us frame goals in terms of what we “should” do instead of what we actually want to do. For example, I’ve heard from many people interested in learning memory techniques because their parents insist they go to medical school.

Someone gave me a “should” when I myself was younger. After dropping out of high school for awhile to deal with similar anxiety and depression issues, someone scolded someone I looked up to highly scolded me. She was being friendly, of course, but she told me I was the kind of person who “should” become a professor. She was aghast that I was at risk of not completely high school at all.

Since she was a professor herself and I basically wanted to be just like her, I carried that image with myself for years. In fact, even years after retiring from working as a professor, I still symbolically fulfil the “should” her words entered into my mind.

Although Dr. Milyavaskaya suggests that the wider psychology of goal pursuit is still in its infancy, when we think reflectively, it’s possible to see just how often we “should” our way into to-do lists and goals we actually don’t want. Spending some time developing mental strength can be very helfpul for avoiding such problems.

Risk Aversion

Although I don’t suffer risk aversion much myself, many people worry about wasting time. For example, I get emails often from people who want to master the Memory Palace technique, but want to get it right the first time.

As a result, they delay the needed experimentation. There are so many skills that you can’t even begin to understand, let alone master, without open exploration.

That’s why I’m glad I don’t have this particular issue. It’s helped me learn many wonderful skills, such as playing music, performing memdeck card magic and learning languages for fun and professional outcomes.

Personal Disorganization

Craig Petty once asked gambling expert and magician Jason Ladanye how he manages to put in so much practice. Ladanye answered with one word: “Organization.”

Ladanye’s also a musician, so his training in deliberate practice was certainly already strong.

But the point is that it’s not about the person. My research into those with the highest IQs show this. It’s about how you organize your time and what you focus on when you practice.

This brings us back to what I discovered in university:

The reading lists were available months in advance.

I also discovered that I could email or call the professors who would be teaching my courses.

As a result of getting the big picture of each course ahead of time, I was able to spend my commute to and from work reading books during the summer. Then, when the semester started, I was so far ahead of the game that I could get my written assignments started straight away.

In other words, I was able to organize the chaos of the school year into a pattern I was able to understand and control.

Even better, I was able to fulfill my urge to complete the tasks because I knew what they were. The Ovsiankina Effect had become my super power and not my enemy.

Other Ways To Leverage The Ovsiankina Effect

Now that you know the main way I’ve found success by understanding why the urge to complete tasks was stressing me out, here are some other ways to get relief from this effect.

As you go through them, understand that not all techniques are useful for everything. But all techniques do benefit from personal exploration and experimentation.

Want Vs. Need Analysis

Before taking on any new area of interest, it’s useful to ask: Is this something I really need, or just something I want?

This simple exercise is useful because we often pile on things we think we want that have nothing to do with fulfilling our basic cognitive needs. As a result, we suffer.

For example, I technically did not need to become a professor in order to pursue my real passion as a writer, but I thought that I did. I’m glad I pushed through and finished my studies, but at the end of the day, I delayed my path to the dream outcome instead of pursuing it directly.

To complete the exercise, simply create two columns on a piece of paper and brainstorm everything that might create an urge to complete a variety of tasks.

I complete this exercise in objective reasoning a few times a year. Knowing what I do now about the Ovsiankina effect, I’ve been able to keep focused on so much of what I actually need to do. By rationally eliminating mere wants, more meaningful accomplishments take place in my life.

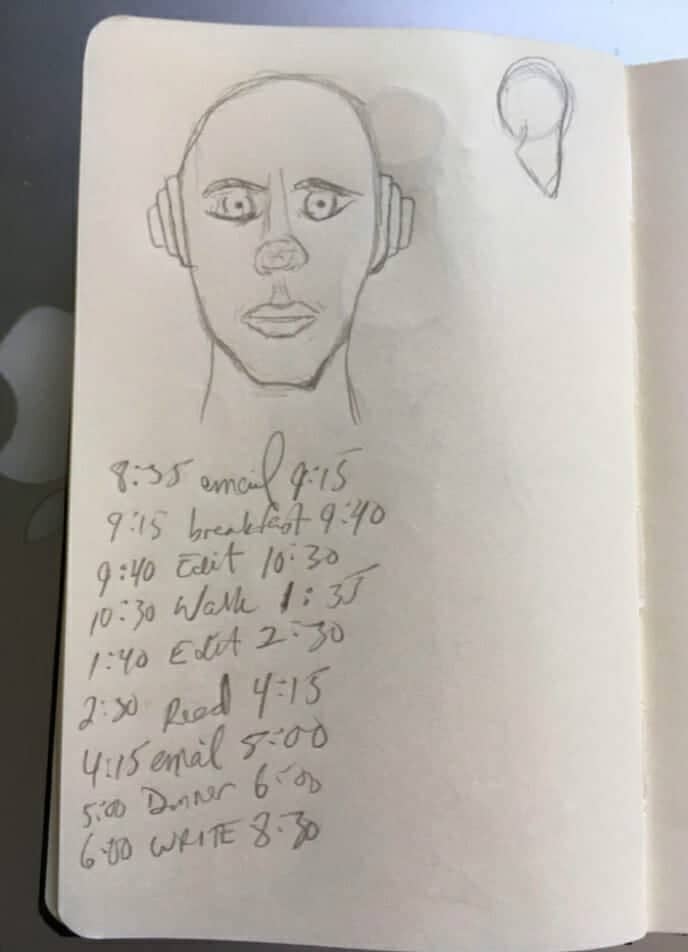

Two: Change How You Schedule Your Time

One thing I’ve learned since graduating is that I no longer have the benefit of courses to structure my time. The only deadlines I have are the ones I give myself.

I’ve found that keeping to-do lists can be avoided altogether by working on lifestyle management.

True, this has a lot to do with how I mindmapped my business and followed a plan that allows me to work from home.

But I still find that it’s easier to manage the Ovsiankina effect by tracking time rather than scheduling it.

To do this, I have changed from writing down the tasks that need completion and memorized them instead. Then, I write down the time I spend on what I’m doing.

Thanks to how procedural and prospective memory operate in the human brain, I’m no longer stressed by the endless things that I have to do. I remember what I did with my time and have a satisfying list of accomplishments at the end of each day.

Three: Environmental Tactics

I just mentioned mind mapping.

One way that I amplify the urge to get things done involves keeping my mind maps visible on my desk until that I’ve completed a task.

After all, the psychology of unfinished tasks is just an effect. It’s not a totality. Sometimes out of sight truly is out of mind.

That’s why I often keep my projects in full view until they are completed.

Likewise, I keep my guitar and playing cards on my desk where I always see them. As a result, I practice far more than if I always put them away.

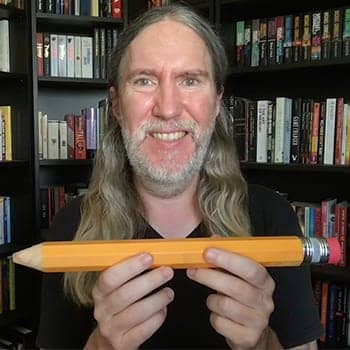

A third example involves how I have used The Freedom Journal to help with language learning and completing books and courses.

Because it’s big and impossible to ignore, it serves as a constant reminder to work on the most important things. It directs the urge to complete tasks in the right direction.

The Skill Of Getting Things Done (Things That Actually Matter)

At the end of the day, most of us are pretty good at getting things done.

It’s just that many of those things aren’t particularly valuable.

Seneca pointed this out a long time ago when he pointed at that we are all too often focused on the “busy stuff” of life instead of actually living it. His point is neither philosophy nor psychology, but something in-between.

But he must have intuitive how the Ovsiankina effect drives us to complete to-do lists that have nothing meaningful on them.

By the way, I quoted this line from Seneca in Latin in this video if you’re interested in hearing what his ancient advice sounded like when he shared it. Memorizing the line itself was something on my to-do lists, and an example of a higher-order task that leads to accomplishment that lasts.

In the age of digital amnesia, we busy ourselves more than ever with things to do of little or no importance.

I hope that by sharing my tactics and strategies, you’ll be able to find some relief from this effect.

And if you’d like more help, training your memory will create more space in your mind to reflect on the many options you have for avoiding the pressures of unfinished tasks.

Sign up here if you like:

Memory training works so well because it expands your short term and working memory.

As a result, you can consider more options, chunk related tasks together with greater ease and keep track of multiple details. You’ll also learn the memorization techniques I used to commit Seneca’s wisdom to memory in Latin.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to enjoy greater mental mastery thanks to your new understanding of this effect?

Make it happen!

Related Posts

- Memory Athlete Braden Adams On The Benefits Of Memory Competition

Braden Adams is one of the most impressive memory athletes of recent times. Learn to…

- Stop Smoking And Boost Memory With These Step-By-Step Addiction Breakers

Want to stop smoking and improve your memory? It might not be easy, but these…

- Episodic Memory And How To Improve It: A Step-By-Step Training Guide

Episodic memory loss is a terrible thing, but luckily there are easy and fun exercises.…