Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

What’s semantic memory? Check this out:

The fact that you know and recognize objects like toast, eggs, and newspaper (without being told each time) is thanks to semantic memory.

However, here’s what semantic memory is not:

Recalling that you had toast and eggs for breakfast yesterday is part of what memory scientists call episodic memory (more about that later).

In this post, I’ll explain what is semantic memory.

Better, you’ll learn why it’s so important, how your brain forms these particular kinds of memories and how can you improve your semantic memory for words and facts specifically.

Here’s exactly what I’ll cover:

Table of Contents

How to Improve Semantic Memory?

Here are 3 simple techniques to improve your semantic memory:

1. Use The Magnetic Memory Method

The easiest and most powerful way to improve your semantic memory, as well as episodic memory, is by learning how to build Memory Palaces using the Magnetic Memory Method.

The Magnetic Memory Method Memory Palace approach is better for remembering and learning than something like mind mapping on its own.

It is an incredible combination of intelligence and memory strengthening tool. Combined with Recall Rehearsal, this holistic process lets you move information from short-term memory into long-term memory faster and with reliable permanence.

What’s more?

You can use all other memory methods inside of Memory Palace, however, you cannot use a Memory Palace inside other memory techniques. This unique approach maximizes the power of the loci method and combines nicely with the pegword method.

All that matters is that you don’t overthink the technique. We all learn it by doing it.

2. Exercise Your Brain

It is essential.

Exercising your brain regularly is the most effective strategy to improve memory and retention.

Memory impairment or memory loss in older adults is common. However, there is a strong relationship between brain exercises and improved cognition and retrieval in older adults.

Numerous tools and exercises can help you to assess your memory and enhance it through games and training exercises. It is a known fact that the more you utilize your neural circuit, the stronger it will get.

This fact can also be applied to numerous neural networks associated with contextual memory, auditory memory, visual memory, short-term memory, working memory, naming, and more.

You can improve your skill of identifying the right word to use for a concept or an object by training the neural network in your brain accordingly.

Here’s a video that will inspire you to use memory techniques and treat them as the ultimate brain exercise.

3. Learn a New Language

When you learn a new language, it requires you to learn and expand new sentence structures, grammar rules, and vocabulary.

Such activities ensure that your semantic memory is continuously being utilized and strengthened as you make progress with the new language.

Here’s a video that helps you learn and memorize the vocabulary of any language.

What is Semantic Memory?

Semantic memory is independent of the context of learning and personal experiences like how we felt at the time the event was experienced or situational properties like time and place of gaining the knowledge.

The level of consciousness associated with semantic memory is noetic because it is independent of context encoding and personal relevance. This was the finding of Endel Tulving in 1985.

For instance, you “know” that Mr. Darcy is a famous character from Pride and Prejudice, which is written by Jane Austen.

You may have read the book, seen the movie or someone may have told you about this character and the author. How you acquired the knowledge and in which context is not essential. What is important is that your semantic memory stored that bit of information as general knowledge.

You can now recall this bit of general knowledge whenever necessary independent of personal experience and of the space or time context in which it was acquired. That is the beauty of your semantic memory.

Usually, the recall semantic memory is automatic when particular information is prompted. However, there might be cases where you have to really think hard about certain facts stored in your semantic memory.

Semantic Memory Definition

Semantic memory is the structured record of facts, ideas, meanings, and concepts about the world that we accumulate throughout our lives and our capacity to recollect this knowledge at will. It is part of your long-term memory.

The breadth of information stored in the semantic memory can range from historical and scientific facts, details of public events, and mathematical equations to the knowledge that allows us to identify objects and understand the meaning of words.

For instance, understanding what the word “memory” means is part of your semantic memory.

Semantic Memory Examples

Memory competitors show their skills with strengthened semantic memory frequently.

For example, they are often asked to memorize vocabulary lists.

Wei Qinru, the 2019 World Memory Champion, memorized 89 random words in 5 minutes.

She also memorized 102 historical dates in 5 minutes, which is an incredible display of recalling semantic information.

Another example is Nigel Richards.

As Scott Young discusses in Ultralearning, Richards is said to have memorized the entire French dictionary in just 9 weeks.

Finally, you use your semantic memory every day.

For example, when you send a text message and add an emoji, the fact that you remember a colon and a parenthesis together means “I’m smiling” draws upon the complexities of semantic memory.

When we draw from the alphabet and a myriad of symbols in everyday reading and communicating online, we are deeply engaging our semantic memory.

Here are a few final examples of semantic memory:

- Naming the state and capital city of your country correctly.

- Knowing that trees give oxygen or fish swim in water.

- Remembering your favorite drink or food or color.

- Being able to understand what the other person is saying.

- Knowing what the words you read mean.

Next, let’s look back to the past.

History of Semantic Memory

Canadian experimental psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Endel Tulving introduced the idea of semantic memory as a distinct memory system in 1972.

Before Tulving, there had not been many in-depth studies or research in the area of human memory.

Tulving outlines these memory types in his book Elements of Episodic Memory. He notes that semantic and episodic differ in how they operate and the types of information they process.

Here’s Tulving’s definition:

Semantic memory is the memory necessary for the use of language. It is a mental thesaurus, organized knowledge a person possesses about words and other verbal symbols…

(Episodic and semantic memory, Tulving E & Donaldson W, Organization of Memory, 1972, New York: Academic Press)

After Tulving, two other experiments noting the differences between episodic and semantic memories were conducted by Kihlstrom (1980) and Jacoby/Dallas (1981).

The study by Jacoby and Dallas was the first to note that implicit memory does not rely on depth of processing as explicit memory does. (Jacoby LL, Dallas M. On the relationship between autobiographical memory and perceptual learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1981)

J.F. Kihlstrom’s study showed that a suggestion for posthypnotic amnesia produced impairments on episodic but not semantic memory tasks. (Kihlstrom, J. F. (1980). Posthypnotic amnesia for recently learned material: Interactions with “episodic” and “semantic” memory. Cognitive Psychology, 12(2), 227-251.)

These experiments paved the way for further investigation into semantic memory.

However, it is only in the last 15 years where interest in semantic memory has greatly increased.

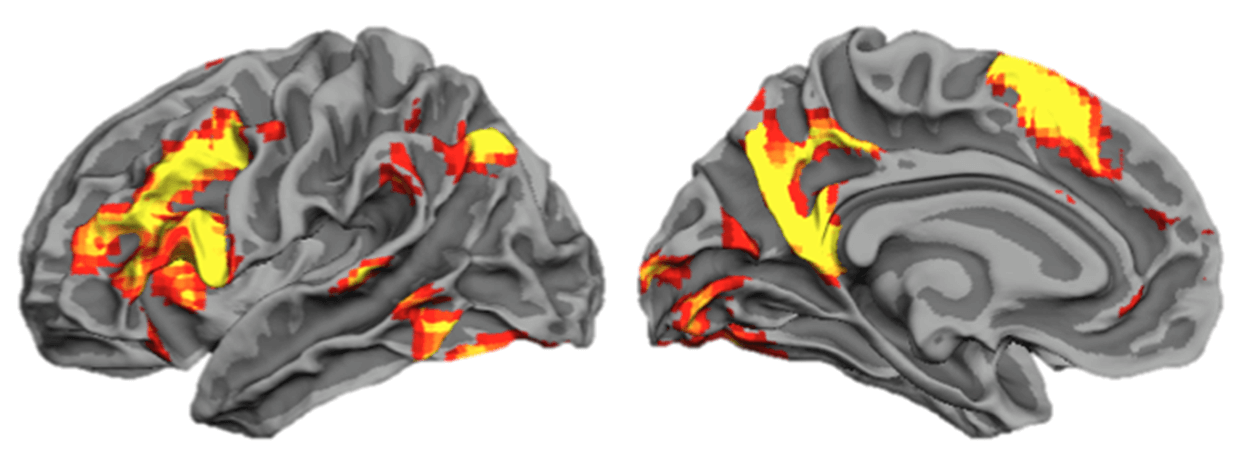

One of the reasons for this newfound interest is an improvement in neuroimaging methods like functional magnetic resonance imaging. These neuroimaging methods reveal that the brain does not have one specific region dedicated to semantic information. Semantic memory is organized throughout the brain.

It is now also known that semantic memory can be divided into separate visual categories such as size, color, and motion. Since specific parts of the brain are responsible for the retrieval of specific semantic memories, semantic memory can be divided into several categories beyond just the visual.

For instance, the parietal cortex retrieves semantic memories of size while the temporal cortex retrieves memories of color. (Explorable.com, Feb 2, 2011, Semantic Memory). There may also be brain areas to consider when it comes to semantic memory on language acquisition.

Is it Different from Episodic Memory?

Absolutely.

Both semantic and episodic memories are part of your long-term memory and are known as declarative memory or explicit memory (memories that can be explained and declared).

However, while an episodic memory involves the conscious recollection of specific events and experiences; semantic memory refers to the mere recollection of nuggets of factual knowledge collected since childhood.

Confused?

Let me simplify it for you.

Episodic memory allows us to consciously recollect past experiences (Tulving, 2002), while semantic memories are devoid of information about personal experience.

For example, to be able to recall what happened during the last football game that you attended is an episodic memory. However, “knowing” that football is a sport without ever watching a game is a semantic memory.

Here’s another example:

When you say “summers in India are hot,” you are drawing that knowledge from your semantic memory.

But when you remember walking down the streets of Delhi on a summer afternoon, licking ice cream, you are drawing on episodic memory.

A Brief Deep Dive Into Types of Memory

We cannot comprehend the entire concept of semantic memory without knowing a bit about the brain and different types of memory.

Your brain has three major components: the cerebrum, the cerebellum, and the brain stem. The cerebrum – responsible for our memory, speech, the senses, and emotional response – is covered by the cerebral cortex (a sheet of neural tissue).

About 90% of our brain’s neurons are located in the cerebral cortex. This cortex is divided into four main regions or lobes – frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe.

Now, the part of the frontal lobe that plays an integral part in processing short-term memories and retaining long-term memories is known as the prefrontal cortex.

When we generally talk of “memory,” it is long-term memory.

However, there are two other memory processes – short-term memory (also called working memory) and sensory memory (it retains sensory information after the original stimuli have ended). These must be worked through before a lasting long-term memory can form.

This model of memory works as a sequence of three stages from sensory to short-term to long-term memory and is known as the Atkinson-Shiffrin model after Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin who developed it in 1968. It is the most popular model for studying memory systems.

Now long-term memory can be further divided into explicit (or declarative) memory and implicit (or procedural) memory.

Declarative memory or explicit memory takes a different definition. It refers to memories that you recall consciously or deliberately. Procedural memory or implicit memory, on the other hand, describes the type of memory that deals with how to do things – like riding a bike or playing the piano.

Here’s a fascinating fact:

The hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and perirhinal cortex encode declarative memories. These are then consolidated and stored in the temporal cortex and other brain regions. Procedural memories, on the other hand, are encoded and stored in specific brain regions – cerebellum, putamen, caudate nucleus, and the motor cortex.

Declarative memory is further subdivided into semantic and episodic memories (now you know the context of our brief deep dive into types of memory).

Another category of declarative memory known as the autobiographical memory, is similar to episodic memory in that both are personal memories from the past. However, while autobiographical memory is more general, for example, when you recall the street name of a house growing up, episodic memory is more specific to time.

Why Is Semantic Memory So Important?

We all need semantic memory to function smoothly in our daily lives. We use it every day to learn, retain, and retrieve new information. It is part of our cognition.

Children and teenagers use it to retain new information that they learn at home or in school, while adults need it to know the sequence of tasks necessary to do their job.

Without semantic memory, you wouldn’t know that the sky is blue or that birds can fly. Your concepts about time and space or meanings of emotions like love and hate are incorporated in your semantic memory.

If your semantic memory is damaged due to any type of disease such as Alzheimer’s disease, you may not be able to identify or name everyday objects, understand the concepts of liberty or know what the word “coffee” means.

There are many benefits to strengthening your semantic memory.

A stronger semantic memory would result in improved long-term memory in students – enabling them to do better in studies.

More importantly, strengthening your semantic memory would enable you to perform better in all aspects of your life without taking vitamins for memory.

How are Semantic Memories Formed?

We all learn new facts, tasks, or concepts from our personal experiences. So, in general, a semantic type of memory is derived from the episodic type of memory.

For example, when you learn a new piece of information, your short-term memory relays it to episodic memory. Initially, you remember the exact time or place where you gathered the information.

However, over time a gradual transition from episodic to semantic memory takes place, where your association of a particular memory to a particular event or stimuli is reduced so that the information is then generalized in your working memory as semantic memory.

When it comes to the encoding process, both semantic and episodic memories have a similar process.

However, semantic memory mainly activates the frontal cortex and temporal cortex, whereas episodic memory activity is concentrated in the hippocampus (amongst many other differences). The other areas of the brain involved in semantic memory use are the left inferior prefrontal cortex and the left posterior temporal area.

Visual, acoustic, and meaning are the three main types of encoding used to commit information to semantic memory.

Individuals may encode information to semantic memory through pictures or reading words and numbers, by repeatedly hearing the information, or by connecting the information to something else that has meaning in the memory.

Different people have different learning styles. One person may do very well with visual aids. Another type of person may encode semantic memory through meaning or repetition.

At the end of the day, there is no single route to semantic memory formation. But you can study better using mnemonics. Just make sure you don’t get into some of the issues we’ll discuss next.

What Affects Semantic Memory?

Some diseases and disorders may cause memory impairments in older adults.

For instance, in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, there may be impairments or deficits in your short-term memory or working memory.

However, as the disease progresses, patients experience more long-term memory loss and deficits, including erosion of episodic and semantic memory.

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease may have difficulty identifying objects or finding words to describe something. They may also suffer from impairments in their ability to recall significant events, such as weddings.

Other types of dementia can also affect short-term memory and long-term memory. For instance, a person with dementia of Alzheimer’s type can find it difficult to store information in the long-term memory, and also can have challenges with retrieval.

Any damage to the medial temporal lobe that plays a critical role in acquiring and retrieving both semantic and episodic memories can also affect your semantic memory.

Studies have also been done on different effects that semantic dementia and herpes simplex virus encephalitis has on semantic memory (Lambon, Lowe, & Rogers, 2007). The study revealed that semantic dementia has a more generalized semantic impairment.

Moreover, amnesic patients also have great difficulty in retaining episodic and semantic information.

Your semantic memory function also is extremely susceptible to cerebral aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

A neuropsychological evaluation can reveal how your brain functions. Neuropsychologists use neuropsychological tests to characterize behavioral and cognitive changes resulting from disorders of the central nervous system or injury, like Parkinson’s disease or other movement disorders.

While you may not be able to protect your memory from all types of diseases, there are ways to improve your memory so that it doesn’t fall victim to age-related memory loss or dementia.

But don’t worry. As Nic Castle found, it’s possible to recover, even from ailments like PTSD.

Higher Attentiveness = Improved Memory

Your relationship with the world around you is dependent on your ability to learn and recall factual knowledge accurately.

Being mindful of the things around you and paying attention when you come across new information is essential to creating long-term memories that can be recalled when necessary.

When you practice mindfulness in everyday activities, you are more attentive. Attentiveness, in turn, helps you encode information better in semantic memory.

Moreover, when you combine attentiveness with the Memory Palace method, your ability to retain and recall factual knowledge is stronger and faster.

If you are interested in the Memory Palace method, please don’t hesitate to get started. I want to help!

Now then, time for a quick test of your semantic memory:

Can you recall the name of the character in the novel I mentioned near the start of this article?

You could, if only you devoted yourself to more memory training. Ready to get started?

Related Posts

- 5 Memory Palace Examples To Improve Your Memory Training Practice

Here are 5 Memory Palace examples that will improve your memory training practice quickly, even…

- How to Memorize Something Fast: 5 Simple Memory Techniques

Wondering how to memorize something fast? Read now for 7 solid steps you can follow…

- Memory Athlete Braden Adams On The Benefits Of Memory Competition

Braden Adams is one of the most impressive memory athletes of recent times. Learn to…

4 Responses

An absolutely amazing podcast Anthony. Got a lot out of it and enjoyed hearing it spoken so poetically by you.

Thanks so much for checking it out, James, and for taking a moment to post. That is much appreciated.

I hope it also gives you some ideas for improving semantic memory amongst all the other levels in your learning life. 🙂

Love that Brain Game video! It’s stunning and tantalising. So much great information in this Anthony – congratulations.

Thanks so much for checking it out, Rosemary.

I’m glad you found the information on this page helpful too. I’m planning to do a lot more memory science for the next while. I think it helps us unpack so many powerful memory exercises and avenues for growth as learners.

Thanks again for all your support of this initiative and look forward to seeing your next post soon! 🙂